Stop me if I've posted this one before. Actually, don't. It's worth re-reading!

"What, however, can possibly link these two other facts: that on the one hand in the 1960s a handful of middle-class connoisseurs successfully combatted headache and eyestrain to achieve, no doubt, an "expanded vision," an attentiveness to the marginal functionings of their own optic system under stimulation and that, on the other, the large plebeian audience of the first ten years of motion pictures put up with a flicker that their social "betters" regarded as such intolerable discomfort that it contributed to their staying away in droves from the places where films were shown ... those smoke-filled, rowdy places frequented exclusively in those days by a class of people for whom motion pictures were cheaper than an evening at the gin mill and no doubt somewhat less uncomfortable than a day spent in the racket and stench of the factory of sweatshop?

"In any but a purely contingent sense, there would seem to be no link at all here, and in fact any attempt to establish one might seem at best ahistoric, at worst grotesque. Yet I have come to regard this encounter as emblem of the contradictory relationships between the cinema of the Primitive Era and the avant-gardes of later periods. For the elimination of flicker and the trembling image, fairly complete after 1909 it seems, was a crucial moment in the realization of the conditions for the emergence of a system of representation complying with the norms of an audience which would include various strata of the bourgeoisie. When the successive modernist movements set about extending, pragmatically or systematically, their "deconstructive" critiques of those representational norms to the realm of film, it was inevitable that sooner or later the flicker should reappear, valued now for both its synthetic and its "self-reflexive" potentials."

--Noel Burch, "Primitivism and the Avant-Gardes: A Dialectical Approach"

Wednesday, November 29, 2006

More Velázquez

Diego Velázquez, La Venus del Espejo (1648-51)

"This nakedness is not, however, an expression of her own feelings; it is a sign of her submission to the owner's feelings or demands. (The owner of both woman and painting.) The painting ... demonstrates this submission ..."

-- John Berger, Ways of Seeing, p.53 (referring to a different painting)

The above image is the figure of a woman who exists for no more reason than the leisurely contemplation and enjoyment of her own beauty, i.e., the satisfaction of herself not as self but as an object of sight. I haven't done enough research to make an educated guess on Velázquez's motives, but regardless of them, I can suggest that the image offers a way out of the unsavory tradition of the Western nude: that by presenting the woman's back to the spectator, and the face as a blurry reflection (also optically impossible), this Venus is presented as obviously an object, immediately and apparently an image for our pleasure and consumption. An iconographic explication of the presence of the mirror might indicate the theme of vanity ... but we can't intuit any emotion or thought to this Venus. She's gazing into a mirror, taking in her own beauty and objecthood, but we are not presented with psychological evidence of her (moral failing of) vanity. She is Image: her Imageness is manifest.

Idle speculation: I have not yet read Deleuze on the Baroque: but if the Baroque is marked by some kind of figure of "the fold," is the productivity of our latter-day engagement with the Baroque marked by our willingness to 'unfold' what was hidden in the folds? That is to say, in the complexity of (say) an image, an oil painting, in the later 17th century, might the interest to us, post-contemporaries, be in the accordion-like flexibility that this furled-up information pack (or stream) provides us? It's what I'll be thinking about in the future. Maybe I'm completely wrong.

Above is an image of Mary "Slasher" Richardson, who attacked the Velázquez with a meat cleaver in 1914. She was a militant suffragette; according to this white nationalist forum page she was also a supporter of the British Union of Fascists and National Socialists.

Tuesday, November 28, 2006

Sharits on YouTube

An excerpt from Paul Sharits' N:O:T:H:I:N:G on YouTube, from a user named 'Afracious.' It seems to take a little while to load, so please be patient!

You can find a lot of his (earlier) stuff on YT, in full or in excerpts, including T,O,U,C,H,I,N,G (the one with the scissors-to-the-tongue). I haven't really watched much of it because of these blurry, artifact-laden transfers on a computer screen simply can't approximate the sheer enveloping force of the flickers projected in a theater. But, as I've mentioned his work periodically in the last few weeks or months, I figured I'd point this out to anyone who may not know anything about Sharits but would be interested in sampling the films (if in a compromised form).

Monday, November 27, 2006

"Ciao, Giovanni"

In Desire (which Rossellini began filming in 1943 but which was finished by Marcello Pagliero in 1946). I don't know how much of Rossellini's work actually survives in the cut shown at MoMA, but it certainly feels like a Rossellini film to me, and a masterpiece, at that. Regardless of who helmed the scene, there's a quick moment where the protagonist Paola (Elli Parvo) is walked home by her gentle Roman beau Giovanni (Carlo Ninchi); she has told him earlier that she has to leave Rome to return to her family's place in the countryside. There's a medium shot of them walking side by side. Cut; they're at the door; Paola's back to us. She turns around and she has tears in her eyes. Absolutely nothing about the composition of the shot or the tonal thrust of the moment centers the tears. If you walked into the theater late and saw this scene immediately you would not even expect tears. But the sudden bursting-forth of this undercurrent, the presentation of a truth beyond appearance, is precisely what Rossellini could get at with incomparable skill.

There are a few shots that look as though they're in slight slow motion; they're incredible.

There is a constant presence of wind and breeze in the outdoor shots.

This film is too beautiful, its beauty is too powerful.

There are a few shots that look as though they're in slight slow motion; they're incredible.

There is a constant presence of wind and breeze in the outdoor shots.

This film is too beautiful, its beauty is too powerful.

Tuesday, November 21, 2006

Counter-Canon: A Viewing List

Let's assume that someone is looking up Schrader's canon online in order to have a nice checklist for the cinema. Perhaps Google or somebody else's website will direct them, in their search, to my blog? My criticism of Schrader's rhetoric and his choices is already up & available, so now what I want to do is propose a counter-canon. Perhaps someone--a budding cinephile, an older person who is just deciding to watch film seriously, an enthusiast of a certain era or genre who wants to branch out more generally--will see Schrader's canon. And there are some great films to see there! But for the purpose of education, encouraging people to see a variety is at least as important as getting them to see The Greats. So that's the first purpose of this list: not to winnow away toward's film art's great core (which I am unconvinced even exists), but to sketch an idea of this medium's powers & parameters. Secondly I want to tweak Schrader's own conception of a rigorous canon. His isn't highbrow by a long shot! There's nothing inherently wrong with middlebrow tastes--unless the person proudly displaying such insists to you that he's got rigorous high standards and a devilishly high brow (as Schrader happens to insist).

These are companions to Schrader's sixty canonical films. Complements; supplements. These don't operate as a canon; they are a counter-canon; they are intended to be watchtowers pointing out towards the parameters. They aren't actually the parameters of cinema's power, though. Except possibly a few of them. I'm only suggesting some new paths to travel, heavily skewed by my tastes. (Even then, frankly, a few films here--the Browning, the Tati, the Eisenstein--do get mentioned in canons sometimes.) When I was whittling down I ended up being least merciful to to Hollywood and French films--which make up the base of my younger cinephilia--because that's what gets the most attention anyway, so there are major films by Sirk, Ray, Walsh, Guitry, even Vigo, etc. "on the cutting room floor." Sixty films in alphabetical order:

3/60 Bäume Im Herbst (Kurt Kren, 1960)

Almost a Man (Vittorio De Seta, 1966)

Les Amours de la pieuvre (Jean Painlevé and Geneviève Hamon, 1965)

L'Ange (Patrick Bokanowski, 1982)

Arigato-san (Hiroshi Shimizu, 1936)

Arsenal (Aleksandr Dovzhenko, 1928)

Barsaat (Raj Kapoor, 1949)

The Bloody Exorcism of Coffin Joe (José Mojica Marins, 1974)

Calabacitas tiernas (Gilberto Martínez Solares, 1949)

Casual Relations (Mark Rappaport, 1973)

Child of the Big City (Yevgeny Bauer, 1915)

The Cloud-Capped Star (Ritwik Ghatak, 1960)

Cockfighter (Monte Hellman, 1974)

Daisies (Vera Chytilova, 1966)

Dark at Noon (Raúl Ruiz, 1993)

Day of the Outlaw (Andre De Toth, 1959)

De cierta manera (Sara Gomez Yera, et al., 1978)

Docteur Chance (F.J. Ossang, 1997)

Edward II (Derek Jarman, 1992)

The End (Christopher Maclaine, 1953)

Forest of Bliss (Robert Gardner and Akos Ostor, 1986)

Freaks (Tod Browning, 1932)

Fuji (Robert Breer, 1974)

Hard Labour on the River Duoro (Manoel de Oliveira, 1931)

A House Divided (Alice Guy-Blaché, 1913)

Las Hurdes (Luis Buñuel, 1932)

Ice (Robert Kramer, 1969)

Images of the World and the Inscription of War (Harun Farocki, 1988)

La Jetée (Chris Marker, 1962)

The Lead Shoes (Sidney Peterson, 1949)

Lettre à Freddy Buache (Jean-Luc Godard, 1981)

Love Streams (John Cassavetes, 1984)

Les Maîtres fous (Jean Rouch, 1955)

Make Way for Tomorrow (Leo McCarey, 1937)

Mandabi (Ousmane Sembene, 1968)

Man with a Movie Camera (Dziga Vertov, 1929)

La Marge (Walerian Borowczyk, 1975)

N:O:T:H:I:N:G (Paul Sharits, 1968)

Paul Tomkowicz--Street-railway Switchman (Roman Kroitor, 1954)

Playtime (Jacques Tati, 1967)

Le Retour à la raison (Man Ray, 1923)

Rose Hobart (Joseph Cornell, 1936)

The Saragossa Manuscript (Wojciech Has, 1965)

Score (Radley Metzger, 1973)

Los siete locos (Leopoldo Torre Nilsson, 1973)

The Store (Frederick Wiseman, 1983)

Strike! (Sergei Eisenstein, 1924)

Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One (William Greaves, 1968)

Take the 5:10 to Dreamland (Bruce Conner, 1976)

The Terrorizer (Edward Yang, 1986)

This Land Is Mine (Jean Renoir, 1943)

Times Square (Allan Moyle, 1981)

A Touch of Zen (King Hu, 1969)

Touki-bouki (Djibril Diop Mambety, 1973)

Tropical Malady (Apichatpong Weerasethakul, 2004)

Videodrome (David Cronenberg, 1983)

Le Voyage à travers l’impossible (Georges Méliès, 1904)

A Walk with Love and Death (John Huston, 1969)

We Won't Grow Old Together (Maurice Pialat, 1972)

Winstanley (Kevin Brownlow and Andrew Mollo, 1975)

... again, this is not a canon. It's not definited by being the "best" (though I did somewhat de facto limit this to films I felt were genuinely great, excellent, or in some cases just very interesting). This list is meant to work in the spirit of enriching canonical lists. This list of worthy films is meant to point out in many different directions: unlike a canon, which gives people a finite list which they can check off one title at a time, this is meant only to suggest to people a great deal more viewing to do, if they so wish. And it is not my purpose to claim that this list is "better" than Schrader's canon, that the films are better, only that it offers a better picture of cinema's possibilities ...

These are companions to Schrader's sixty canonical films. Complements; supplements. These don't operate as a canon; they are a counter-canon; they are intended to be watchtowers pointing out towards the parameters. They aren't actually the parameters of cinema's power, though. Except possibly a few of them. I'm only suggesting some new paths to travel, heavily skewed by my tastes. (Even then, frankly, a few films here--the Browning, the Tati, the Eisenstein--do get mentioned in canons sometimes.) When I was whittling down I ended up being least merciful to to Hollywood and French films--which make up the base of my younger cinephilia--because that's what gets the most attention anyway, so there are major films by Sirk, Ray, Walsh, Guitry, even Vigo, etc. "on the cutting room floor." Sixty films in alphabetical order:

3/60 Bäume Im Herbst (Kurt Kren, 1960)

Almost a Man (Vittorio De Seta, 1966)

Les Amours de la pieuvre (Jean Painlevé and Geneviève Hamon, 1965)

L'Ange (Patrick Bokanowski, 1982)

Arigato-san (Hiroshi Shimizu, 1936)

Arsenal (Aleksandr Dovzhenko, 1928)

Barsaat (Raj Kapoor, 1949)

The Bloody Exorcism of Coffin Joe (José Mojica Marins, 1974)

Calabacitas tiernas (Gilberto Martínez Solares, 1949)

Casual Relations (Mark Rappaport, 1973)

Child of the Big City (Yevgeny Bauer, 1915)

The Cloud-Capped Star (Ritwik Ghatak, 1960)

Cockfighter (Monte Hellman, 1974)

Daisies (Vera Chytilova, 1966)

Dark at Noon (Raúl Ruiz, 1993)

Day of the Outlaw (Andre De Toth, 1959)

De cierta manera (Sara Gomez Yera, et al., 1978)

Docteur Chance (F.J. Ossang, 1997)

Edward II (Derek Jarman, 1992)

The End (Christopher Maclaine, 1953)

Forest of Bliss (Robert Gardner and Akos Ostor, 1986)

Freaks (Tod Browning, 1932)

Fuji (Robert Breer, 1974)

Hard Labour on the River Duoro (Manoel de Oliveira, 1931)

A House Divided (Alice Guy-Blaché, 1913)

Las Hurdes (Luis Buñuel, 1932)

Ice (Robert Kramer, 1969)

Images of the World and the Inscription of War (Harun Farocki, 1988)

La Jetée (Chris Marker, 1962)

The Lead Shoes (Sidney Peterson, 1949)

Lettre à Freddy Buache (Jean-Luc Godard, 1981)

Love Streams (John Cassavetes, 1984)

Les Maîtres fous (Jean Rouch, 1955)

Make Way for Tomorrow (Leo McCarey, 1937)

Mandabi (Ousmane Sembene, 1968)

Man with a Movie Camera (Dziga Vertov, 1929)

La Marge (Walerian Borowczyk, 1975)

N:O:T:H:I:N:G (Paul Sharits, 1968)

Paul Tomkowicz--Street-railway Switchman (Roman Kroitor, 1954)

Playtime (Jacques Tati, 1967)

Le Retour à la raison (Man Ray, 1923)

Rose Hobart (Joseph Cornell, 1936)

The Saragossa Manuscript (Wojciech Has, 1965)

Score (Radley Metzger, 1973)

Los siete locos (Leopoldo Torre Nilsson, 1973)

The Store (Frederick Wiseman, 1983)

Strike! (Sergei Eisenstein, 1924)

Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One (William Greaves, 1968)

Take the 5:10 to Dreamland (Bruce Conner, 1976)

The Terrorizer (Edward Yang, 1986)

This Land Is Mine (Jean Renoir, 1943)

Times Square (Allan Moyle, 1981)

A Touch of Zen (King Hu, 1969)

Touki-bouki (Djibril Diop Mambety, 1973)

Tropical Malady (Apichatpong Weerasethakul, 2004)

Videodrome (David Cronenberg, 1983)

Le Voyage à travers l’impossible (Georges Méliès, 1904)

A Walk with Love and Death (John Huston, 1969)

We Won't Grow Old Together (Maurice Pialat, 1972)

Winstanley (Kevin Brownlow and Andrew Mollo, 1975)

... again, this is not a canon. It's not definited by being the "best" (though I did somewhat de facto limit this to films I felt were genuinely great, excellent, or in some cases just very interesting). This list is meant to work in the spirit of enriching canonical lists. This list of worthy films is meant to point out in many different directions: unlike a canon, which gives people a finite list which they can check off one title at a time, this is meant only to suggest to people a great deal more viewing to do, if they so wish. And it is not my purpose to claim that this list is "better" than Schrader's canon, that the films are better, only that it offers a better picture of cinema's possibilities ...

Schrader 2: Electric Boogaloo

I wasn't incredibly impressed with Paul Schrader's article on the cinema canon (thoughts here). He has responded to his critics here. (Also, someone signing as 'schrader' did post a comment in reply to my original criticisms, but the person--he, if it was indeed Paul Schrader himself--declined to address my thoughts, answering the great Jen MacMillan only, perhaps because he's decided I'm not worth addressing. Fair enough.) In Film Comment now, the man writes:

"I wrote the article in reaction to this, attempting to look back at the Century of Cinema with a cold eye and a very high brow."

Schrader's canon is the definition of middlebrow, not highbrow. This is basically an inarguable fact about his choices as far as I see it. His canon offers us nothing new: he's reiterating a standard greatest hits list of a decently educated middlebrow film buff contingent, as any Film Comment reader has doubtless already seen countless times in places like Sight & Sound. He adds a slight personal twist by including films like The Big Lebowski or Talk to Her instead of absolutely anything that is short, nonfiction, or avant-garde. Apparently Schrader would have us believe that highbrows hew to the mainstream feature fiction film and nothing else. Ha! (And he happily owns up to the charge of Eurocentrism in the process, weirdly enough.) I wrote a huge draft in response to Schrader's own response to his critics, but I've basically deleted it. I made a lot of my major points already and I don't want to keep harping on them. Instead I want to offer something positive instead of further rants. For anyone young or new to cinema who might google 'Schrader's canon' in order to look up films, and who might come across this page, I'm going to offer a counter-canon. To me, adherence to a canon is less important than instilling/encouraging comprehension, critical thinking, curiosity (three c-phrases I prefer to "canon," now that I think of it) as far as pedagogy and film culture are concerned. Instead of the films Schrader's chosen, I'm choosing deliberately less well-known, offbeat, perverse, even strenuously imperfect "b-sides." Some of them are greater, perhaps much greater, than their counterparts though. But as I've said, I do love some of his choices, so other b-side choices are not meant as replacements but rather as supplements or complements. I'll see if I can get a counter-gold section up tonight.

"I wrote the article in reaction to this, attempting to look back at the Century of Cinema with a cold eye and a very high brow."

Schrader's canon is the definition of middlebrow, not highbrow. This is basically an inarguable fact about his choices as far as I see it. His canon offers us nothing new: he's reiterating a standard greatest hits list of a decently educated middlebrow film buff contingent, as any Film Comment reader has doubtless already seen countless times in places like Sight & Sound. He adds a slight personal twist by including films like The Big Lebowski or Talk to Her instead of absolutely anything that is short, nonfiction, or avant-garde. Apparently Schrader would have us believe that highbrows hew to the mainstream feature fiction film and nothing else. Ha! (And he happily owns up to the charge of Eurocentrism in the process, weirdly enough.) I wrote a huge draft in response to Schrader's own response to his critics, but I've basically deleted it. I made a lot of my major points already and I don't want to keep harping on them. Instead I want to offer something positive instead of further rants. For anyone young or new to cinema who might google 'Schrader's canon' in order to look up films, and who might come across this page, I'm going to offer a counter-canon. To me, adherence to a canon is less important than instilling/encouraging comprehension, critical thinking, curiosity (three c-phrases I prefer to "canon," now that I think of it) as far as pedagogy and film culture are concerned. Instead of the films Schrader's chosen, I'm choosing deliberately less well-known, offbeat, perverse, even strenuously imperfect "b-sides." Some of them are greater, perhaps much greater, than their counterparts though. But as I've said, I do love some of his choices, so other b-side choices are not meant as replacements but rather as supplements or complements. I'll see if I can get a counter-gold section up tonight.

Dissembling Now!

Exhibit A:

Exhibit B:

Exhibit C:

I'm not trying to bear pretensions toward knowing anything out of the ordinary about race and racism--because I surely don't--but this Michael Richards incident has come out at just the time that I've been reading and thinking a lot about images and conceptions of blackness in my country's cinema and popular culture--obviously. So. The problem I have here is the widespread cultural assumption--basically held by white people--that being a racist is almost an "occupation," that Michael Richards can claim with a straight face that he's "not a racist," yet that that these words just "bubbled up." (Perhaps had he dropped the N-bomb alone one could chalk it up to a racist action merely fueled by a misguided attempt to "shock," as though he were just following in the fearless footsteps of Lenny Bruce or Richard Pryor. But the furious, and initial invocation of a lynching murder--a fork up your ass!?--just confirms something deeper.) This is the sort of irrational mentality that justifies statements like, "I'm not racist, but..." But what? As though pre-emptively asserting that you're not a racist nullifies the vicious idiocy of the racist statement you're about to make?

One of those trashy reality TV shows--was it an episode of America's Next Top Model?--had one white "contestant" (or should we 'fess up and just call them characters?) spewing racist cant: no dreaded "n-words" if I recall, but a lot of stupidity about (y'know) those types of people--welfare mothers, FUBU clothing, all the regular caricatures promoted by Limbaugh-types. When some of the other contestants called her on this, including, particularly, a black woman, this racist insisted to the other contestants that they couldn't accuse her of racism because she knew in her heart that she wasn't racist, you see, and since they couldn't know the state of her soul as well as she did, they couldn't be sure that she was a racist. This is the belief: that being a racist can only, strictly mean one who actively lynches blacks people, uses racial slurs openly, and willfully admits that he or she thinks whites are superior to all others. Nobody else is racist by this illogic: actually racist behavior, for instance, is by the same token dismissed as 'mistakes,' 'accidents,' 'misunderstood actions.' Never for what it is. (I believe the unsavory aspirant was eliminated early from the model comptetition, by the way.) In an interview Stephen Colbert said to Tim Robbins recently, "You're white, right, 'cause I can't tell, you know. Race doesn't matter to me, I can't even see a person's color." A typical rallying cry for my fellow whites well-caricatured by Colbert there.

So look at the spectacle we have before us recently with regards to Michael Richards' outburst. I'll handsomely wager he doesn't have a KKK hood in his closet. He's not some vigorous, full-time, Aryan Nation-style racist. But his behavior is simply an outcropping of deep-seated racism embedded in the power structure of this society (which his "apology" very vaguely acknowledged, albeit as a way of rationalizing his actions). What interests me also is that Jerry Seinfeld was so shocked and saddened by this outburst (and the forthright, unignorable racism of a certain word), but as the Danny Hoch video above demonstrates, he is no angel either as far as the propogation of racism in art and media. It's not enough to allude, as Richards does, to some kind of wounded Zeigeist which we need to heal--that's true enough, in its cloudy ethereal way--but to also identify those instances, material and recognizable instances or practices, when this racism against all people of color comes through in ways less immediate and blatant (to nonwhites) than a single word, like "nigger." Racism also means something like "Ramon." Nonwhite individuals & communities of course are sensitive to these instances, already, and have long been. How can they help get the rest of us to pay attention?

Exhibit B:

Exhibit C:

I'm not trying to bear pretensions toward knowing anything out of the ordinary about race and racism--because I surely don't--but this Michael Richards incident has come out at just the time that I've been reading and thinking a lot about images and conceptions of blackness in my country's cinema and popular culture--obviously. So. The problem I have here is the widespread cultural assumption--basically held by white people--that being a racist is almost an "occupation," that Michael Richards can claim with a straight face that he's "not a racist," yet that that these words just "bubbled up." (Perhaps had he dropped the N-bomb alone one could chalk it up to a racist action merely fueled by a misguided attempt to "shock," as though he were just following in the fearless footsteps of Lenny Bruce or Richard Pryor. But the furious, and initial invocation of a lynching murder--a fork up your ass!?--just confirms something deeper.) This is the sort of irrational mentality that justifies statements like, "I'm not racist, but..." But what? As though pre-emptively asserting that you're not a racist nullifies the vicious idiocy of the racist statement you're about to make?

One of those trashy reality TV shows--was it an episode of America's Next Top Model?--had one white "contestant" (or should we 'fess up and just call them characters?) spewing racist cant: no dreaded "n-words" if I recall, but a lot of stupidity about (y'know) those types of people--welfare mothers, FUBU clothing, all the regular caricatures promoted by Limbaugh-types. When some of the other contestants called her on this, including, particularly, a black woman, this racist insisted to the other contestants that they couldn't accuse her of racism because she knew in her heart that she wasn't racist, you see, and since they couldn't know the state of her soul as well as she did, they couldn't be sure that she was a racist. This is the belief: that being a racist can only, strictly mean one who actively lynches blacks people, uses racial slurs openly, and willfully admits that he or she thinks whites are superior to all others. Nobody else is racist by this illogic: actually racist behavior, for instance, is by the same token dismissed as 'mistakes,' 'accidents,' 'misunderstood actions.' Never for what it is. (I believe the unsavory aspirant was eliminated early from the model comptetition, by the way.) In an interview Stephen Colbert said to Tim Robbins recently, "You're white, right, 'cause I can't tell, you know. Race doesn't matter to me, I can't even see a person's color." A typical rallying cry for my fellow whites well-caricatured by Colbert there.

So look at the spectacle we have before us recently with regards to Michael Richards' outburst. I'll handsomely wager he doesn't have a KKK hood in his closet. He's not some vigorous, full-time, Aryan Nation-style racist. But his behavior is simply an outcropping of deep-seated racism embedded in the power structure of this society (which his "apology" very vaguely acknowledged, albeit as a way of rationalizing his actions). What interests me also is that Jerry Seinfeld was so shocked and saddened by this outburst (and the forthright, unignorable racism of a certain word), but as the Danny Hoch video above demonstrates, he is no angel either as far as the propogation of racism in art and media. It's not enough to allude, as Richards does, to some kind of wounded Zeigeist which we need to heal--that's true enough, in its cloudy ethereal way--but to also identify those instances, material and recognizable instances or practices, when this racism against all people of color comes through in ways less immediate and blatant (to nonwhites) than a single word, like "nigger." Racism also means something like "Ramon." Nonwhite individuals & communities of course are sensitive to these instances, already, and have long been. How can they help get the rest of us to pay attention?

Monday, November 20, 2006

Image of the Day

I "discovered" Willem Drost in a course on Dutch & Flemish painting I took in college. I prefer his version of Bathsheba (1654) to his master's (although I have never been to the Louvre and have never seen either in the paint). The roundness of the forms of this solitary woman, placed within an asymmetrical composition, makes for a very subtly unsettling image--as though balance has just been lost.

Rated X by an All-White Jury

So Tuwa saw Sweet Sweetback's Baadasssss Song the other day, and following his lead, so did I (this was my second viewing). Why the crazy film grammar? I haven't done the research that might give us a really satisfactory answer, but let me speculate a little first, then I'll post a few facts about the film's production. Maybe a little later down the line I'll post more with some reading under my belt.

It's interesting that this film has come up on EL just at the same time I've posted the Sharits image (and, uh, "dialogue excerpt") from T,O,U,C,H,I,N,G. We know, and can trace, the loose netting of connections between the low culture 'generic' or 'exploitation' film by the very late 1950s or early 1960s into the 1970s and those of the high culture 'modernist' (including, even, 'structuralist' or 'materialist') cinema of the same time. The experimental elements of classy Metzger (a swingin' and cocktail-slingin' Resnais) or trashy Meyer (a Mojave desert trucker-Eisenstein), for instance. A fellow cinephile on the Net, many months ago, suggested I check out Vernon Zimmerman and Andrew Meyer, who both began in the a-g but moved into exploitation. Andy Milligan? Jack Smith? So many possibilities, and I'm only mentioning (mainly) American work thus far. Sweet Sweetback boasts a straightforward narrative through-line: Sweetback, who has had a tough live but possesses great sexual prowess, is sold out in a to-be-minor way by his (black) employer, only to "break," and find himself on the run from the police.

Moment to moment, though, the film is disjointed, repetitive, "crunchy" rather than smooth. At one point in the film a woman complains about how, when her children get old and bad, the government takes them away from her--she might have had one named Leroy, but she can't rightly recall. On the soundtrack her couple of lines are replayed, with slight variation as to where they might stop or begin, at least a half a dozen times. What's the reason for something like this? What's the rationale behind stray cuts and nonlinear throwaway footage in Melvin Van Peebles' film? I would suggest that it's got something to do with whatever also inspired the likes of Snow. For this question I'm moved to suggest that the issue at hand isn't one of Everest-like aesthetic experimentation "trickling down" from the contemporaneous high-cinematic heroes of Manny Farber and Peter Wollen circa 1971 to the supposedly lower forms of Russ Meyer's bosomania and MVP's struggles against The Man. Rather it's a multi-front assault, where fringes of popular cinema--the trashy, the generic, the rebellious--working on, in their own way, the sorts of problems that artists like Sharits, Snow, et al. are expressing at the same time. (Again, let me emphasize I'm dealing mostly with an "American" scene--North American, if you will--for convenience's sake more than anything else.)

Sweet Sweetback is dangerous in part because it doesn't connect its critique of racism to a nice narrative that we can enjoy thoughtlessly ("we" here meaning white viewers, at least; I can only idly imagine how various non-white audiences saw and see the film). It's a brutal narrative, a story about ruthless domination, relentless pursuit, and unsolicited survivalism. The story almost has to be fractured on an experiential level (and simplified on a conceptual one) in order to deliver the real ... I hesitate, but: meaning ... of the film. That is to say, the tool of the three- or five-act narrative, with three-dimensional characterization, seamless pacing and continuity editing, which historically suits the fiction feature film so well, is usefully fractured in this particular fiction feature film because it renders more palpable the offenses dealt to its characters (and by association "The Black Community," credited as stars in the film, of course); it depicts more nakedly the structures and enactment of racial aggression and domination that whites, particularly powerful whites and their servant classes whether brain or brawn (not all white characters in the film are "enemies" though), carry out. The narrative doesn't carry us, we have to sit and watch each abuse, hear each sad or angry line, for what they are--and as pulled stitches out of what we may prefer to be a seamless narrative.

In short, my preliminary guess as to why Melvin Van Peebles made this film the way he did is that the techniques offered a utilitarian solution to his expression of flight, struggle, and solidarity in the face of the American racial/social structure. This is not to say that I think MVP didn't also have strong aesthetic interests in such techniques, too: he might have, much like someone like Sharits. But the pragmatic usefulness of these techniques seems to me to be a pretty unavoidable justification. (I haven't seen Story of a Three Day Pass yet, but the more traditional film Watermelon Man seemed pretty unsuccessful to me. It's worth seeing if it falls within one's personal or scholarly interests, of course, but I can't say it's quite as damning and--this is important--motivating an indictment of American race relations as Sweetback is.)

* * *

"Stating that what major studies like Columbia Pictures, which had offered him a three-picture contract, called a little control he called extreme control, Van Peebles dropped the contract to make a "revolutionary" and independent film. Produced for $50,000--the money he had earned as director of Columbia's Watermelon Man, a loan of $50,000 from Bill Cosby, and funds from nonindustry sources--Van Peebles's $500,000 production, Sweet Sweetback's Baadasssss Song (1970) changed the course of African American film production and the depiction of African Americans on screen. ... Unlike the experience of Gordon Parks with Warner Bros., Van Peebles avoided paying film industry craft union wages by claiming to be producing a porno picture. He also wrote and directed the film and composed the music, in addition to playing the leading man. Released through Cinemation, initially in only two theaters, one in Detroit and one in Atlanta, Sweetback grossed over $10 million in its first run."

-- Jesse Algernon Rhines, Black Film/White Money. Rutgers UP, 1996. p. 43-44. [Sic on the figures mentioned, by the way. I think that the first $50K might be a typo, that is, $500K?]

It's interesting that this film has come up on EL just at the same time I've posted the Sharits image (and, uh, "dialogue excerpt") from T,O,U,C,H,I,N,G. We know, and can trace, the loose netting of connections between the low culture 'generic' or 'exploitation' film by the very late 1950s or early 1960s into the 1970s and those of the high culture 'modernist' (including, even, 'structuralist' or 'materialist') cinema of the same time. The experimental elements of classy Metzger (a swingin' and cocktail-slingin' Resnais) or trashy Meyer (a Mojave desert trucker-Eisenstein), for instance. A fellow cinephile on the Net, many months ago, suggested I check out Vernon Zimmerman and Andrew Meyer, who both began in the a-g but moved into exploitation. Andy Milligan? Jack Smith? So many possibilities, and I'm only mentioning (mainly) American work thus far. Sweet Sweetback boasts a straightforward narrative through-line: Sweetback, who has had a tough live but possesses great sexual prowess, is sold out in a to-be-minor way by his (black) employer, only to "break," and find himself on the run from the police.

Moment to moment, though, the film is disjointed, repetitive, "crunchy" rather than smooth. At one point in the film a woman complains about how, when her children get old and bad, the government takes them away from her--she might have had one named Leroy, but she can't rightly recall. On the soundtrack her couple of lines are replayed, with slight variation as to where they might stop or begin, at least a half a dozen times. What's the reason for something like this? What's the rationale behind stray cuts and nonlinear throwaway footage in Melvin Van Peebles' film? I would suggest that it's got something to do with whatever also inspired the likes of Snow. For this question I'm moved to suggest that the issue at hand isn't one of Everest-like aesthetic experimentation "trickling down" from the contemporaneous high-cinematic heroes of Manny Farber and Peter Wollen circa 1971 to the supposedly lower forms of Russ Meyer's bosomania and MVP's struggles against The Man. Rather it's a multi-front assault, where fringes of popular cinema--the trashy, the generic, the rebellious--working on, in their own way, the sorts of problems that artists like Sharits, Snow, et al. are expressing at the same time. (Again, let me emphasize I'm dealing mostly with an "American" scene--North American, if you will--for convenience's sake more than anything else.)

Sweet Sweetback is dangerous in part because it doesn't connect its critique of racism to a nice narrative that we can enjoy thoughtlessly ("we" here meaning white viewers, at least; I can only idly imagine how various non-white audiences saw and see the film). It's a brutal narrative, a story about ruthless domination, relentless pursuit, and unsolicited survivalism. The story almost has to be fractured on an experiential level (and simplified on a conceptual one) in order to deliver the real ... I hesitate, but: meaning ... of the film. That is to say, the tool of the three- or five-act narrative, with three-dimensional characterization, seamless pacing and continuity editing, which historically suits the fiction feature film so well, is usefully fractured in this particular fiction feature film because it renders more palpable the offenses dealt to its characters (and by association "The Black Community," credited as stars in the film, of course); it depicts more nakedly the structures and enactment of racial aggression and domination that whites, particularly powerful whites and their servant classes whether brain or brawn (not all white characters in the film are "enemies" though), carry out. The narrative doesn't carry us, we have to sit and watch each abuse, hear each sad or angry line, for what they are--and as pulled stitches out of what we may prefer to be a seamless narrative.

In short, my preliminary guess as to why Melvin Van Peebles made this film the way he did is that the techniques offered a utilitarian solution to his expression of flight, struggle, and solidarity in the face of the American racial/social structure. This is not to say that I think MVP didn't also have strong aesthetic interests in such techniques, too: he might have, much like someone like Sharits. But the pragmatic usefulness of these techniques seems to me to be a pretty unavoidable justification. (I haven't seen Story of a Three Day Pass yet, but the more traditional film Watermelon Man seemed pretty unsuccessful to me. It's worth seeing if it falls within one's personal or scholarly interests, of course, but I can't say it's quite as damning and--this is important--motivating an indictment of American race relations as Sweetback is.)

* * *

"Stating that what major studies like Columbia Pictures, which had offered him a three-picture contract, called a little control he called extreme control, Van Peebles dropped the contract to make a "revolutionary" and independent film. Produced for $50,000--the money he had earned as director of Columbia's Watermelon Man, a loan of $50,000 from Bill Cosby, and funds from nonindustry sources--Van Peebles's $500,000 production, Sweet Sweetback's Baadasssss Song (1970) changed the course of African American film production and the depiction of African Americans on screen. ... Unlike the experience of Gordon Parks with Warner Bros., Van Peebles avoided paying film industry craft union wages by claiming to be producing a porno picture. He also wrote and directed the film and composed the music, in addition to playing the leading man. Released through Cinemation, initially in only two theaters, one in Detroit and one in Atlanta, Sweetback grossed over $10 million in its first run."

-- Jesse Algernon Rhines, Black Film/White Money. Rutgers UP, 1996. p. 43-44. [Sic on the figures mentioned, by the way. I think that the first $50K might be a typo, that is, $500K?]

Sunday, November 19, 2006

Image of the Day

"Destroy. Destroy. Destroy. Destroy. Destroy. Destroy. Destroy. Destroy..." (And check out this.)

Friday, November 17, 2006

Introductory Ramblings Through Images

Eventually I hope to turn this train of thought into something. Anyway, a clumsy start:

(The Scar of Shame, 1927, directed by Frank Peregini. I understand Micheaux's predominant theme was 'passing'--I've only seen one for myself; this similarly seminal film of the silent black American cinema, on the other hand, is foremost about class and color tone divisions among black people exclusively, if I recall.)

Fred Hampton after he was murdered by the police.

Superfly.

"Don't fuck with Pam Grier," we are told forcefully enough by images like these.

What I'd like to suggest, one topic or tangent I want to introduce, is the question of black Americans' "space of their own" in cinema--that means literally on-screen but also in terms of exhibition or consumption. There was the cinema of Micheaux and up through Spencer Williams, Jr.--respectable cinema, or so I suppose its reputation holds, for and usually by black people. The 1960s (David Ehrenstein relates here that Billy Wilder's The Apartment was a watershed moment for the hiring of black extras in H'wood, by the way) had what I figure to be an entrenchment of two dominant cinematic/media image-sets of blackness in America. There is blackness as a well-behaved victim (child or chaste adult), Mockingbird blackness, Poitier blackness: truly dignified at best, horribly condescending and racist at worst. Perhaps both at the same time, quite often. Then there is blackness as a threat, very strong and masculine and separatist: the Black Panthers, for instance. I could be wrong about this: I'm still a fumbling student of the issue: but it's my impression at the moment.

The black exploitation film as a tool in the process of social control?--better for a dominant white class to peddle fantasies of black power to black audiences after so many of its political leaders had been assassinated, than to have said leaders making real strides. What became "blaxploitation" started off as a tool, an expression, of black individuals and communities. Melvin Van Peebles made Sweet Sweetback's Baadasssss Song ('71) on his own. And it was attuned to something deep, powerful. But around the same time, Hollywood was allowing black people to finally make their own films--under the aegis of Hollywood and its money, presumably for black audiences, but not independent for themselves. Gordon Parks made the first such film in The Learning Tree ('69, a good film though I saw it years ago, don't recall it too well). Blaxploitation soon became a moneymaking tool for your standard, white-owned, white-run companies. Black actors starred in movies (at least nominally?) targeted to black viewers, but by and large I don't believe these films produced for the black community/ies of America.

What I want to critique--assuming there are not parts of the equation which I have yet to discover which would negate the basic criticism--is the exploitation of distinctly black film workers and audiences for distinctly white profit. But. I don't want to dismiss this genre altogether for the circumstances of its production. I want to look into it, see more than the handful of films I have already seen, figure out what it says and what it might say. I would like to learn to what extent, and in what nature, the genre might have been a genuine "space" of black Americans' own. I have a decent initial grasp of the available bibliography, but if there are hidden gems to be read (or seen), please let me know. I also did not see Mario Van Peebles' recent documentary, though I will. This is the foundation: what I want to go into is analysis (or even "poetics"--a non-Bordwellian sort of film poetics?) ...

* * *

... and ... on the nature of Elusive Lucidity these days, I have to admit that I am apprehensive of alienating the small group of people who read this blog. I am grateful for any and all readers I have (though at the same time I basically dislike bringing up my work to people who don't know about it: I feel the only readers I earn are those who find me and decide the writing is worth a return peek). I know that this is essentially a cinema blog. And I want to keep this a cinema blog, because if I am good at keeping a blog about anything, it must be that. But for months now (actually, really, maybe it's a process of years) I have felt a mounting personal pressure about politics, and greater and greater self-resentment for not doing anything about it. I feel a paralysis because of this--a paralysis of my creative and analytical faculties both. When I read sites like Venezuelanalysis, Brownfemipower, Corpwatch, or countless others, I am overcome with the urge to have my own meager screen musings online reflect the passion & hopefully commitment that these sites--these people--inspire in me. (As to how well I translate that into real life, too, well, that's another part of the challenge.) I make zero apologies for my politics; at the same time I make zero demands of my readers, politically. I understand that there are a few conservatives and libertarians, and probably a majority of liberals/Democrats, among my readership, and I consider myself none of these. So in discussing moving images I hope that my hospitality and my convictions work together organically, and I hope that I can essentially, eventually do more than preach to a choir either politically- or cinephilically-speaking. There--that's off my chest with #201.

(The Scar of Shame, 1927, directed by Frank Peregini. I understand Micheaux's predominant theme was 'passing'--I've only seen one for myself; this similarly seminal film of the silent black American cinema, on the other hand, is foremost about class and color tone divisions among black people exclusively, if I recall.)

Fred Hampton after he was murdered by the police.

Superfly.

"Don't fuck with Pam Grier," we are told forcefully enough by images like these.

What I'd like to suggest, one topic or tangent I want to introduce, is the question of black Americans' "space of their own" in cinema--that means literally on-screen but also in terms of exhibition or consumption. There was the cinema of Micheaux and up through Spencer Williams, Jr.--respectable cinema, or so I suppose its reputation holds, for and usually by black people. The 1960s (David Ehrenstein relates here that Billy Wilder's The Apartment was a watershed moment for the hiring of black extras in H'wood, by the way) had what I figure to be an entrenchment of two dominant cinematic/media image-sets of blackness in America. There is blackness as a well-behaved victim (child or chaste adult), Mockingbird blackness, Poitier blackness: truly dignified at best, horribly condescending and racist at worst. Perhaps both at the same time, quite often. Then there is blackness as a threat, very strong and masculine and separatist: the Black Panthers, for instance. I could be wrong about this: I'm still a fumbling student of the issue: but it's my impression at the moment.

The black exploitation film as a tool in the process of social control?--better for a dominant white class to peddle fantasies of black power to black audiences after so many of its political leaders had been assassinated, than to have said leaders making real strides. What became "blaxploitation" started off as a tool, an expression, of black individuals and communities. Melvin Van Peebles made Sweet Sweetback's Baadasssss Song ('71) on his own. And it was attuned to something deep, powerful. But around the same time, Hollywood was allowing black people to finally make their own films--under the aegis of Hollywood and its money, presumably for black audiences, but not independent for themselves. Gordon Parks made the first such film in The Learning Tree ('69, a good film though I saw it years ago, don't recall it too well). Blaxploitation soon became a moneymaking tool for your standard, white-owned, white-run companies. Black actors starred in movies (at least nominally?) targeted to black viewers, but by and large I don't believe these films produced for the black community/ies of America.

What I want to critique--assuming there are not parts of the equation which I have yet to discover which would negate the basic criticism--is the exploitation of distinctly black film workers and audiences for distinctly white profit. But. I don't want to dismiss this genre altogether for the circumstances of its production. I want to look into it, see more than the handful of films I have already seen, figure out what it says and what it might say. I would like to learn to what extent, and in what nature, the genre might have been a genuine "space" of black Americans' own. I have a decent initial grasp of the available bibliography, but if there are hidden gems to be read (or seen), please let me know. I also did not see Mario Van Peebles' recent documentary, though I will. This is the foundation: what I want to go into is analysis (or even "poetics"--a non-Bordwellian sort of film poetics?) ...

* * *

... and ... on the nature of Elusive Lucidity these days, I have to admit that I am apprehensive of alienating the small group of people who read this blog. I am grateful for any and all readers I have (though at the same time I basically dislike bringing up my work to people who don't know about it: I feel the only readers I earn are those who find me and decide the writing is worth a return peek). I know that this is essentially a cinema blog. And I want to keep this a cinema blog, because if I am good at keeping a blog about anything, it must be that. But for months now (actually, really, maybe it's a process of years) I have felt a mounting personal pressure about politics, and greater and greater self-resentment for not doing anything about it. I feel a paralysis because of this--a paralysis of my creative and analytical faculties both. When I read sites like Venezuelanalysis, Brownfemipower, Corpwatch, or countless others, I am overcome with the urge to have my own meager screen musings online reflect the passion & hopefully commitment that these sites--these people--inspire in me. (As to how well I translate that into real life, too, well, that's another part of the challenge.) I make zero apologies for my politics; at the same time I make zero demands of my readers, politically. I understand that there are a few conservatives and libertarians, and probably a majority of liberals/Democrats, among my readership, and I consider myself none of these. So in discussing moving images I hope that my hospitality and my convictions work together organically, and I hope that I can essentially, eventually do more than preach to a choir either politically- or cinephilically-speaking. There--that's off my chest with #201.

Thursday, November 16, 2006

Varia

The following picture is credited here as the oldest color photograph. 1872.

This is the 200th post on Elusive Lucidity. Some things I'd like to put here in the reasonably near future include thoughts on aliens, colonial adventurers, those who take up cameras as if they were guns, the longer processes of the 1970s black exploitation movie (deliberate emphasis on exploitation as a separate word), Modigliani, Soviet formalism, the Baroque, and more stray thoughts on corporeality. In between I still need to figure out just how to cope with things like this, and the fact that I'm staying afloat in life while people in Palestine, Oaxaca, Iraq, and also even here at home are facing unspeakable hardship and brutality. We'll see how it all goes.

This is the 200th post on Elusive Lucidity. Some things I'd like to put here in the reasonably near future include thoughts on aliens, colonial adventurers, those who take up cameras as if they were guns, the longer processes of the 1970s black exploitation movie (deliberate emphasis on exploitation as a separate word), Modigliani, Soviet formalism, the Baroque, and more stray thoughts on corporeality. In between I still need to figure out just how to cope with things like this, and the fact that I'm staying afloat in life while people in Palestine, Oaxaca, Iraq, and also even here at home are facing unspeakable hardship and brutality. We'll see how it all goes.

Wednesday, November 15, 2006

Torino 5

Olaf and I discussed film museums early in the festival. I consider myself a spiritual child of Henri Langlois and have always been fascinated by the notion of a film museum. For many years I have drooled over Langlois' immense Cinematheque book with the photos of his original museum designs. I have been to film museums – in New York (AMMI) and Spain (Girona) – but nothing prepared me for what I saw yesterday here in Torino.

Now, Olaf objects to the museumification of cinema –"only the projected image can keep cinema alive!" –, but admits that he has a problem with museums in general. I, on the other hand, looked forward to my first open afternoon to go the Museo Nazionale del Cinema, which I had heard was the greatest film museum in the world and reason alone to visit Turin. When friend andf ellow Torino blogger Neil Young said he was going, two mornings ago over breakfast, I joined him. I probably looked like a lost schoolboy in this place as I wandered around in utter wonderment. Another purifying experience of many in Torino. Here are a few pics, more to follow…

Now, Olaf objects to the museumification of cinema –"only the projected image can keep cinema alive!" –, but admits that he has a problem with museums in general. I, on the other hand, looked forward to my first open afternoon to go the Museo Nazionale del Cinema, which I had heard was the greatest film museum in the world and reason alone to visit Turin. When friend andf ellow Torino blogger Neil Young said he was going, two mornings ago over breakfast, I joined him. I probably looked like a lost schoolboy in this place as I wandered around in utter wonderment. Another purifying experience of many in Torino. Here are a few pics, more to follow…

1. The main lobby, with the giant figure from CABIRIA. br>

3. The museum is hosted inside of one of Turin's mos tfascinating structures, the Mole Antonelliana. Inside is a suspended glass elevator, almost like Willy Wonka's, that goes to the top of the building. Here is the view pointing directly up.

--Gabe Klinger

Torino 4

Friends, amici: the festival, I am happy to report, has been a non-stop freight train of cinematic delights. However, the idea of sitting in front of a computer for an extended period of time has seemed less and less appealing as my days here are turning into hours and minutes… My wish, now, is to savor every bit so that I can share many exciting things in the coming week. For now I couldn't resist posting these two stories from the growing backlog, both occurring today, November 15th:

- Festival co-director Roberto Turigliatto, at my solicitation, introduces me to French cinema thinker extraordinaire Jean Douchet. Humbled, I ramble a few words in French and then ask, in an attempt to dig myself out of an embarrassing monologue of incomprehensible compliments, if he speaks English. Douchet responds, sardonically (in French), "No, I'm one of the few Frenchman who doesn't speak other languages." I make a second attempt at French, this time telling him simply that I'm an admirer of his writings and that I have some friends who speak very highly of him as a person. This was plain enough, and voilà, Douchet understood, immediately turning to the person next to him and saying, "This young man has paid me a very nice compliment!" The person stuck his hand out to greet me. And that person, who had escaped my vision though I knew was lurking around somewhere, was, to my rapture, Claude Chabrol.

- Yesterday I phoned the cheery and obliging staff of the international press office to see if I could get an interview with Nanni Moretti, in town promoting his latest film, Il Caimano. Though I haven't seen the film, I wanted to talk to him anyway, as a lover of his early oeuvre. One of the fest employees, Martin, told me that Moretti wasn't doing any interviews, bu tthat he would inquire. Since I hadn't heard from Martin, I lost hope. Today, however, I spotted Moretti having a coffee in the Cinema Ambrosio. I wanted to tell him that his La Messa è finita is one of my twenty or so favorite movies (which is absolutely true). He, like Douchet, also doesn't speak English. And I stumble much harder in Italian than I do in French. Luckily there was someone around to translate. Moretti's response was, "What are the other films you like?" I thought he was referring to his own films, soI said, "Palombella Rossa, Ecce Bombo, Bianca—" "No, no, no…" Moretti said shaking his head, "What are the other films on your list of twenty?" So I said, "Well, Ozu's Early Summer, Bresson's Balthazar-—""Basta,basta [enough, enough]…" Moretti interrupted again, "I just wanted to know if I was in good company."

Olaf -- who, to answer Zach, likely sees more than 400 new films a year (though I will ask to be sure) was standing next to me. I asked him to take a picture of us, and, well... Olaf's exemplary camera skills can be seen below:

--Gabe Klinger

- Festival co-director Roberto Turigliatto, at my solicitation, introduces me to French cinema thinker extraordinaire Jean Douchet. Humbled, I ramble a few words in French and then ask, in an attempt to dig myself out of an embarrassing monologue of incomprehensible compliments, if he speaks English. Douchet responds, sardonically (in French), "No, I'm one of the few Frenchman who doesn't speak other languages." I make a second attempt at French, this time telling him simply that I'm an admirer of his writings and that I have some friends who speak very highly of him as a person. This was plain enough, and voilà, Douchet understood, immediately turning to the person next to him and saying, "This young man has paid me a very nice compliment!" The person stuck his hand out to greet me. And that person, who had escaped my vision though I knew was lurking around somewhere, was, to my rapture, Claude Chabrol.

- Yesterday I phoned the cheery and obliging staff of the international press office to see if I could get an interview with Nanni Moretti, in town promoting his latest film, Il Caimano. Though I haven't seen the film, I wanted to talk to him anyway, as a lover of his early oeuvre. One of the fest employees, Martin, told me that Moretti wasn't doing any interviews, bu tthat he would inquire. Since I hadn't heard from Martin, I lost hope. Today, however, I spotted Moretti having a coffee in the Cinema Ambrosio. I wanted to tell him that his La Messa è finita is one of my twenty or so favorite movies (which is absolutely true). He, like Douchet, also doesn't speak English. And I stumble much harder in Italian than I do in French. Luckily there was someone around to translate. Moretti's response was, "What are the other films you like?" I thought he was referring to his own films, soI said, "Palombella Rossa, Ecce Bombo, Bianca—" "No, no, no…" Moretti said shaking his head, "What are the other films on your list of twenty?" So I said, "Well, Ozu's Early Summer, Bresson's Balthazar-—""Basta,basta [enough, enough]…" Moretti interrupted again, "I just wanted to know if I was in good company."

Olaf -- who, to answer Zach, likely sees more than 400 new films a year (though I will ask to be sure) was standing next to me. I asked him to take a picture of us, and, well... Olaf's exemplary camera skills can be seen below:

--Gabe Klinger

Monday, November 13, 2006

Torino 3

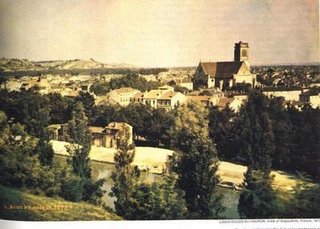

Turner and Crary

"The work of Goethe, Schopenhauer, Ruskin, and Turner and many others are all indications that by 1840 the process of perception itself had become, in various ways, a primary object of vision. For it was this very process that the functioning of the camera obscura kept invisible. Nowhere else is the breakdown of the perceptual model of the camera obscura more decisively evident than in the late work of Turner. Seemingly out of nowhere, his painting of the late 1830s and 1840s signals the irrevocable loss of a fixed source of light, the dissolution of a cone of light rays, and the collapse of the distance separating an observer from the site fo optical experience. Instead of the immediate and unitary apprehension of an image, our experience of a Turner painting is lodged amidst an inescapable temporality. ... The sfumato of Leonardo, which had generated during the previous three centuries a counter-practice to the dominance of geometrical optics, is suddenly and overwhelmingly triumphant in Turner. But the substantiality he gives to the void between objects and his challenges to the integrity and identity of forms now coincides with a new physics: the science of fields and thermodynamics."

-- Jonathan Crary, Techniques of the Observer (p. 138)

Wondering how to best figure this out so that I understand it viscerally: the historical chain of scientific progress, particularly in optics, opened up huge doors in our (Western) comprehension of visual and mental perception. By the time Impressionism rolled around, artists could claim this inspiration as physical, optical fact and inspiration. Eventually that proved not to be a satisfying parameter--the artists of 20th century modernism shaped the materials art to fit in visual perception their mental perceptions, i.e., expressionism in any and all of its forms. The movement from Impressionism to Expressionism was one that opened to floodgates of the mind/eye to science, then pushed the deluge back out into the world ...

(Sorry if the formatting is bad here.)

Sunday, November 12, 2006

Torino 2

First day in Turin

I'll try to avoid talking about the common maladies one has at a film festival— that is, insomnia (bed is such a waste of time when there are drinks and conversations to be had on the day's films!), sleepiness (see previous), malnutrition (stuffing one's face at the hotel breakfast certainly doesn't suffice for the entire day), dehydration (one word: booze), and the many anxieties about getting to films on time and such. A plentitude of these "difficulties"will naturally appear in the off-space of this blog, and perhaps in between the lines when I start to turn in cranky reviews of otherwise pretty decent films.

And now, into worthier digressions…

My first images of the Piedmont region, glimpsed from the plane window, were the Alps' peaks cutting throughthe settling clouds. When I got to Turin, I wandered for a while trying to get a better look at the surrounding nature. By the time I found what seemed to be *the* view – facing a portion of the city that rests on a mountain and which reminded me of Barcelona's Montjuic neighborhood – it dawned on me that the press office would be closing and I wouldn't be able to get my badge. I made it just in time, but when I got there I was told that my credentials were waiting for me at the hotel. The festival kindly offered a temporary solution, furnishing me with an invitation for whichever film I wished to see that night. Running into festival co-director Giulia D'Agnolo Vallan, who assembled this year's complete Robert Aldrich retrospective, it became clear that the program to catch was Emperor of the North (Pole)*. A great print, Giulia advertised, and Keith Carradine and Ernest Borgnine would be there!

It was no surprise to see Olaf "The Shadow" near the front of the line. Olaf's last appearance on this blog was in late January. He continues to elude my camera (here he hides behind a tote bag for the Isola filmfestival in Slovenia):

McMahonist that he is, Olaf sat in front – refusing "to miss a single grain". Borgnine was in the crowd, unmistakable. Introducing the film, he and Carridine spoke elegantly in Italian, Carradine noting (and I'm translating roughly here), "When I made this film I was a young man. He [pointing to Borgnine] not so much." Borgnine, 89, kept saying "Grazie per tutti" ("thank you for everything"), a warmness projecting from his big gap-toothed smile. The audience applauded and applauded – in fact, I've never seen an audience applaud so much (even at individual credits in the film's opening).

In the film, Borgnine transforms his trademark smile into a psychopathic grin: playing Shack, a railway conductor on an Oregon line dubbed "Emperor of the North Pole", he's a harrowing villain. The only man to match him is Lee Marvin's Number 1, a veteran hobo whose last ambition in life is to jump the Emperor undetected. Shack is introduced hurling a hammer at a hobo trespasser, provoking the hobo's gruesome dismemberment under the train wheels. Indeed, Shack manages to turn a variety of ordinary objects into deathly torture devices: chains, wood planks, cargo pins are employed memorably to expel drifters. Number 1 and Cigaret (Carradine), an apprentice rail jumper, mostly deflect Shack – who clearly enjoys taking his no hobo policy to homicidal heights – with their ow ntricks, the result of years of experience on the rails (the film takes place at the apex of the Great Depression).

A viable parallel to Aldrich's filmmaking – Emperor especially – is the Chinese martial arts film. In both, characters function within a world of strict macho codes. Their often violent and disruptive acts are carried out with formal grace and precision that relate to a fabricated morality, which makes the films fun to watch because the audience doesn't feel implicated in the bloodlust of the characters. Aldrich and the great D.P. Joseph Biroc are endlessly inventive in exploring the compositional and rhythmic possibilities of the action – one scene in particular, set entirely in a thick fog, is a triumph of atmospheric lighting and might be closer to something like the avant-garde Le Tempestaire by Jean Epstein than any Hollywood film of the period.

Emperor of the North is an action film in the truest sense, when such a thing was still delightfully uncompromised (the only recent Hollywood film that even comes close to Aldrich's mastery in its mano-a-mano action is Friedkin's The Hunted). Emperorof the North is also a film about trains, which takes us back to Lumière, Bitzer, Medvedkin, etc. At a crowded pub afterwards, meeting up with three colleagues from Slovenia, Nika, Nil, and Maya, we assigned metaphors to trains in cinema, such as the impression of the film strip speeding through light… A layman eavesdropper would likely role their eyes at such poetic critical discourse. But it's endearing, especially among a group of seasoned critics, to see such simple passion. Here's where we all share something essential about the history of cinema.

* The film's title, onscreen, appears as Emperor of the North, though the film is apparently more widely known under Aldrich's original title, Emperor of the North Pole.

--Gabe Klinger

I'll try to avoid talking about the common maladies one has at a film festival— that is, insomnia (bed is such a waste of time when there are drinks and conversations to be had on the day's films!), sleepiness (see previous), malnutrition (stuffing one's face at the hotel breakfast certainly doesn't suffice for the entire day), dehydration (one word: booze), and the many anxieties about getting to films on time and such. A plentitude of these "difficulties"will naturally appear in the off-space of this blog, and perhaps in between the lines when I start to turn in cranky reviews of otherwise pretty decent films.

And now, into worthier digressions…

My first images of the Piedmont region, glimpsed from the plane window, were the Alps' peaks cutting throughthe settling clouds. When I got to Turin, I wandered for a while trying to get a better look at the surrounding nature. By the time I found what seemed to be *the* view – facing a portion of the city that rests on a mountain and which reminded me of Barcelona's Montjuic neighborhood – it dawned on me that the press office would be closing and I wouldn't be able to get my badge. I made it just in time, but when I got there I was told that my credentials were waiting for me at the hotel. The festival kindly offered a temporary solution, furnishing me with an invitation for whichever film I wished to see that night. Running into festival co-director Giulia D'Agnolo Vallan, who assembled this year's complete Robert Aldrich retrospective, it became clear that the program to catch was Emperor of the North (Pole)*. A great print, Giulia advertised, and Keith Carradine and Ernest Borgnine would be there!

It was no surprise to see Olaf "The Shadow" near the front of the line. Olaf's last appearance on this blog was in late January. He continues to elude my camera (here he hides behind a tote bag for the Isola filmfestival in Slovenia):

McMahonist that he is, Olaf sat in front – refusing "to miss a single grain". Borgnine was in the crowd, unmistakable. Introducing the film, he and Carridine spoke elegantly in Italian, Carradine noting (and I'm translating roughly here), "When I made this film I was a young man. He [pointing to Borgnine] not so much." Borgnine, 89, kept saying "Grazie per tutti" ("thank you for everything"), a warmness projecting from his big gap-toothed smile. The audience applauded and applauded – in fact, I've never seen an audience applaud so much (even at individual credits in the film's opening).

In the film, Borgnine transforms his trademark smile into a psychopathic grin: playing Shack, a railway conductor on an Oregon line dubbed "Emperor of the North Pole", he's a harrowing villain. The only man to match him is Lee Marvin's Number 1, a veteran hobo whose last ambition in life is to jump the Emperor undetected. Shack is introduced hurling a hammer at a hobo trespasser, provoking the hobo's gruesome dismemberment under the train wheels. Indeed, Shack manages to turn a variety of ordinary objects into deathly torture devices: chains, wood planks, cargo pins are employed memorably to expel drifters. Number 1 and Cigaret (Carradine), an apprentice rail jumper, mostly deflect Shack – who clearly enjoys taking his no hobo policy to homicidal heights – with their ow ntricks, the result of years of experience on the rails (the film takes place at the apex of the Great Depression).

A viable parallel to Aldrich's filmmaking – Emperor especially – is the Chinese martial arts film. In both, characters function within a world of strict macho codes. Their often violent and disruptive acts are carried out with formal grace and precision that relate to a fabricated morality, which makes the films fun to watch because the audience doesn't feel implicated in the bloodlust of the characters. Aldrich and the great D.P. Joseph Biroc are endlessly inventive in exploring the compositional and rhythmic possibilities of the action – one scene in particular, set entirely in a thick fog, is a triumph of atmospheric lighting and might be closer to something like the avant-garde Le Tempestaire by Jean Epstein than any Hollywood film of the period.

Emperor of the North is an action film in the truest sense, when such a thing was still delightfully uncompromised (the only recent Hollywood film that even comes close to Aldrich's mastery in its mano-a-mano action is Friedkin's The Hunted). Emperorof the North is also a film about trains, which takes us back to Lumière, Bitzer, Medvedkin, etc. At a crowded pub afterwards, meeting up with three colleagues from Slovenia, Nika, Nil, and Maya, we assigned metaphors to trains in cinema, such as the impression of the film strip speeding through light… A layman eavesdropper would likely role their eyes at such poetic critical discourse. But it's endearing, especially among a group of seasoned critics, to see such simple passion. Here's where we all share something essential about the history of cinema.

* The film's title, onscreen, appears as Emperor of the North, though the film is apparently more widely known under Aldrich's original title, Emperor of the North Pole.

--Gabe Klinger

An Afternoon in New York

(Ed. note--Gabe Klinger returns to Elusive Lucidity with some more festival reports. This is a prologue to Torino.)

A New York whirlwind: my presence barely registered on the city, but in a mere six hours I managed to lunch with Zach – persuading him once again to host me on Elusive Lucidity –, visit my friend Nemo on the Harlem set of his new movie (where I also met Hope, the super-hero lead), chat with the wonderful Sara Driver in Soho, and meet a former Chicago chum, Andy, for a beer on Bowery. If you're lucky enough to have the option, New York is the perfect place to charge one's batteries before a festival trip. Just standing on the corner of Spring and Lafayette waiting for Andy to arrive I felt awakened by the purposeful bustle of the human traffic, a steady stream of excited faces that left me wondering, enviously, what each and every person on the street was going off to.

To follow: first impressions of Turin, an encounter with Olaf, Robert Aldrich's Emperor of the North, and drinks with the Slovenian critical contingent

An incredible autumn day in New York.

Zach Campbell, illustrious blog owner

In Harlem: Nemo and his mantle of pictoral curios.

Hope: a super-hero in uniform

At nightfall: a cig with Sara in the park

Andy on Bowery. A farewell beer...

Departure from JFK.

--Gabe Klinger

A New York whirlwind: my presence barely registered on the city, but in a mere six hours I managed to lunch with Zach – persuading him once again to host me on Elusive Lucidity –, visit my friend Nemo on the Harlem set of his new movie (where I also met Hope, the super-hero lead), chat with the wonderful Sara Driver in Soho, and meet a former Chicago chum, Andy, for a beer on Bowery. If you're lucky enough to have the option, New York is the perfect place to charge one's batteries before a festival trip. Just standing on the corner of Spring and Lafayette waiting for Andy to arrive I felt awakened by the purposeful bustle of the human traffic, a steady stream of excited faces that left me wondering, enviously, what each and every person on the street was going off to.

To follow: first impressions of Turin, an encounter with Olaf, Robert Aldrich's Emperor of the North, and drinks with the Slovenian critical contingent

An incredible autumn day in New York.

Zach Campbell, illustrious blog owner

In Harlem: Nemo and his mantle of pictoral curios.

Hope: a super-hero in uniform

At nightfall: a cig with Sara in the park

Andy on Bowery. A farewell beer...

Departure from JFK.

--Gabe Klinger

Thursday, November 09, 2006

More on Winstanley (the Film)

"As a result, there is a strangeness to the whole thing, an unfamiliarity. This is not just because its story is not well known to the general viewer. There are other reasons. The occasional explanatory intertitles are reduced to frustratingly brief captions to the action, affording but little information beyond the immediacy of the scene. The acting, particularly from the nonprofessional actors, seems tentative and uncertain; as a result, characters themselves seem unaccountably unaware of their Historical Significance. Some of the characters, particularly Will Everard and Captain Gladman, come and go, appearing and disappearing, abruptly and unexpectedly, their contextual significance unremarked. Winstanley himself is a cipher, a genial but baffling torrent of high-flown rhetoric, prayer, and common sense. Finally, to put a rather whimsical point to it, the storyline at times does not seem aware of where it is going or what kind of narrative shape it is assuming. At times it just drifts, blithely unaware of its own portentousness, refusing to explain itself, frequently denying our demand for quick and easy meanings.

"While freely admitting that some of these qualities stem directly from budgetary constraints and the inexperience of the crew, Brownlow defends this admittedly rough-hewn quality, particularly with regard to the use of nonprofessional actors. "Any conviction is killed as soon as most profession actors start 'acting,'" he says, "and this is the trouble with the kind of film Andrew and I like to make. They are supposed to show events that are happening while you watch them, as opposed to enacted historical pageants. If you don't feel these people are real and convincing, ... then we have failed." It is the very absence of calculation and professional polish, adds Brownlow, that is to be desired.

"Winstanley thus belongs to a select company of history films that is rare in the cinema. While it reconstructs a vanished world that displays what historian Simon Schama describes as "an unruly completeness," it also "challenges the truisms of linear history, where the order of events is progressive in both a temporal and a moral sense." In sume, continues Schama:

"These are the films that have respected the strangeness of the past, and have accepted that the historical illumination of the human condition is not necessarily going to be an edifying exercise. ... These are also films that embrace history for its power to complicat, rather than clarify, and warn the time traveler that he is entering a place where he may well lose the thread rather than get the gist."

...