I. New FilmsVery few new films adorn my personal film viewing log in '06--but one film among a very small sample rose to a really high level for me, Hong Sang-soo's The Woman on the Beach. II. (Re)Viewing of the YearLove Streams, 35mm, at the Anthology Film Archives.III. Old Films Seen on CelluloidBelow is a very rough preferential list. Differences between individual spots are basically negligible--just understand that I liked #1 more than #21, and cherished all of them. One film per filmmaker, and also an understanding that in several cases the film chosen is sort of a 'peak' stand-in for two or ten works by that artist.

1. La Prise de pouvoir au Louis XIV (Roberto Rossellini, 1966) MoMA2. Sátántangó (Béla Tarr, 1994) MoMA3. Arnulf Rainer (Peter Kubelka, 1960) Whitney [... also, a corrolary: Tony Conrad's The Flicker]4. The Last Movie (Dennis Hopper, 1971) Anthology5. N:O:T:H:I:N:G (Paul Sharits, 1968) Anthology6. Fuji (Robert Breer, 1974) Anthology 7. The Story of the Late Chrysanthemums (Kenji Mizoguchi, 1939) Film Forum8. Forest of Bliss (Robert Gardner and Akos Ostor, 1986) MoMA9. The Text of Light (Stan Brakhage, 1974) Anthology10. Report (Bruce Conner, 1967) Anthology11. The Lead Shoes (Sidney Peterson, 1949) Anthology12. China 9, Liberty 37 (Monte Hellman, 1979) BAM13. Ice (Robert Kramer, 1969) Anthology14. Chumlum (Ron Rice, 1964) Anthology15. Les Amours de la pieuvre (Jean Painlevé and Geneviéve Hamon, 1965) Whitney16. In Spring (Mikhail Kaufman, 1929) Walter Reade17. L'Amour fou (Jacques Rivette, 1968) Moving Image18. Echoes of Silence (Peter Emanuel Goldman, 1967) Anthology19. Puce Moment (Kenneth Anger, 1949) Anthology20. La Villa dei mostri (Michelangelo Antonioni, 1949) BAM21. A Walk with Love and Death (John Huston, 1969) MoMAIV. Old Films Seen on VideoA special mention should be made to online places like UbuWeb, providing a sampling forum for unfortunately scarce works of fringe or experimental cinema (and like Mubarak Ali mentioned in his recent year-end commentary, Toshio Matsumoto's works are fascinating). Below are the same rules as above, but with a few more classics that I only saw in 2006. Long live the game of Humiliation.

1. La Prise de pouvoir au Louis XIV (Roberto Rossellini, 1966) MoMA2. Sátántangó (Béla Tarr, 1994) MoMA3. Arnulf Rainer (Peter Kubelka, 1960) Whitney [... also, a corrolary: Tony Conrad's The Flicker]4. The Last Movie (Dennis Hopper, 1971) Anthology5. N:O:T:H:I:N:G (Paul Sharits, 1968) Anthology6. Fuji (Robert Breer, 1974) Anthology 7. The Story of the Late Chrysanthemums (Kenji Mizoguchi, 1939) Film Forum8. Forest of Bliss (Robert Gardner and Akos Ostor, 1986) MoMA9. The Text of Light (Stan Brakhage, 1974) Anthology10. Report (Bruce Conner, 1967) Anthology11. The Lead Shoes (Sidney Peterson, 1949) Anthology12. China 9, Liberty 37 (Monte Hellman, 1979) BAM13. Ice (Robert Kramer, 1969) Anthology14. Chumlum (Ron Rice, 1964) Anthology15. Les Amours de la pieuvre (Jean Painlevé and Geneviéve Hamon, 1965) Whitney16. In Spring (Mikhail Kaufman, 1929) Walter Reade17. L'Amour fou (Jacques Rivette, 1968) Moving Image18. Echoes of Silence (Peter Emanuel Goldman, 1967) Anthology19. Puce Moment (Kenneth Anger, 1949) Anthology20. La Villa dei mostri (Michelangelo Antonioni, 1949) BAM21. A Walk with Love and Death (John Huston, 1969) MoMAIV. Old Films Seen on VideoA special mention should be made to online places like UbuWeb, providing a sampling forum for unfortunately scarce works of fringe or experimental cinema (and like Mubarak Ali mentioned in his recent year-end commentary, Toshio Matsumoto's works are fascinating). Below are the same rules as above, but with a few more classics that I only saw in 2006. Long live the game of Humiliation.

1. Numéro deux (Jean-Luc Godard, 1975)2. Au hasard, Balthazar (Robert Bresson, 1966)3. Vampyr (Carl Theodor Dreyer, 1932)4. Ali--Fear Eats the Soul (Rainer Werner Fassbinder, 1974)5. Viva La Muerte (Fernando Arrabal, 1971)6. Barsaat (Raj Kapoor, 1949)7. Edward II (Derek Jarman, 1992)8. Dark at Noon (Raúl Ruiz, 1993)9. There Was a Father (Yasujiro Ozu, 1942)10. Diary of a Chambermaid (Luis Buñuel, 1964)11. The Battle of Algiers (Gillo Pontecorvo, 1965)12. These Hands (Florence M'mbugu-Schelling, 1988)13. Monsieur Klein (Joseph Losey, 1976)14. Salt of the Earth (Herbert J. Biberman, 1954)15. No Room for the Groom (Douglas Sirk, 1952)16. Les Filles de Kamaré (René Vienet, 1974)17. Love Affair, or the Case of the Missing Switchboard Operator (Dušan Makavejev, 1967)18. Family Diary (Valerio Zurlini, 1962)19. The Hired Hand (Peter Fonda, 1971)20. Dead or Alive: Final (Takashi Miike, 2002)21. The Saragossa Manuscript (Wojciech Has, 1965)V. Film BookJonathan Beller's The Cinematic Mode of Production I suppose. Truly important, I will write more on it in the future, in the meantime interested readers will want to check out Le Colonel Chabert, who's posted a few recent entries dealing with the book.VI. LaughingRevisitation: The Happiest Days of Your Life (Frank Launder, 1950) - One of the funniest films ever, if you ask me.New on Film: For Your Consideration (Christopher Guest, 2006) - Specifically, Fred Willard with his fauxhawk, and the scene where the Siskel & Ebert clones unexpectedly reach an agreement--the articulation of the moment of exaggerated shock is small & priceless. (I still haven't seen Borat and have no idea what I'll think of it.)A Moment out of Time: When Sho Aikawa buys a hungry kid about five bowls of noodles in Dead or Alive: Final, and as the kid slurps away our hero nonchalantly states, "Finish it or I'll kill you." I wonder if my reaction is similar to a Japanese speaker's.

What follows are slightly pointless and solipsistic musings. Avast, read at your own risk!

Sports #1: Fisticuffs

I'm not a boxing fan exactly, but I found this article interesting (I found it at some political blog I was surfing very recently, but I'm too lazy to double check which one at the moment). The media treatment of Mike Tyson finds itself echoed strongly by the underappreciated Walter Hill-directed Snipes/Rhames vehicle Undisputed ('02). Armond White wrote up the film in a positive review here. It's hard for me to deal with White's reviews these days--his weird permutation of rightist authoritarian populism is now too demoralizing--but for a while he seemed to be one of the few name reviewers engaging with ideas when he wrote on films, and at the time (2001-2002: he also seemed more aligned with the social left then, tho' I could be wrong) I was really inspired by his work. And anyway the article and the film offer another occasion to recommend Mandingo, Richard Fleischer's 1976 film maudit which is sensationalist, and far from a masterpiece, but still quite an important film. David Ehrenstein (for the record--gay and black like Mr. White, but in his case a figure on the left) has called it the "most honest film about American racism ever made."

Sports #2: Football (the English kind)

This is the first season I've had cable and channels that showed European club soccer. Before, I was the most fairweather sort of soccer fan imaginable--very occasional club matches, highlights clips, whatever friendlies I could catch on ESPN, and of course the World Cup. (I could never afford to go to bars to watch games, either--not to the extent that I could follow a team.) But after a (happy) year without cable my girlfriend and I finally got it last summer--the kicker as far as I was concerned was that it was time for the World Cup. Now I find that I'm addicted. I could give up otherwise fine/useful channels like news networks, TCM, IFC, Bravo (Project Runway), even maybe the Food Network, but to give up Fox Soccer Channel seems like the biggest loss to imagine. At any rate, being able to follow along with the English Premier League this season, I've finally decided which team I want to get behind: Arsenal. I'm not a supporter, not even really a true fan: just a guy who's chosen somebody to cheer for when watching a certain league. It's the fact that they're dedicated to a beautiful team game that seals it. Or, as my friend and occasional EL contributer Gabe reformulated it to me last time he was here in New York (Arsenal were playing Chelsea): "It's aesthetics versus consumerism." Anyway, I just thought I'd mention that.

Music

When it comes to contemporary music I am pretty clueless. But post-breakthrough (not always sophomore) efforts from the recent folkish-indie "scene" have left me cold (e.g., the second one by Iron & Wine). I didn't know how I'd feel about Joanna Newsom's Ys. It took me a while to get into her voice but once I did I was hooked by The Milk-Eyed Mender. "Peach Plum Pear" has to be my favorite song from the (for lack of a better word) 'indie' scene in the past several years (unless Animal Collective's "Winters Love" tops it). Anyway I just picked up Ys and am listening to it now and--whew--it's awesome!

Cinema Theater as Sleeping Compartment

What is the suggested etiquette for waking up someone behind you who is snoring through a film screening? Being a nonconfrontational person I tried "excuse me, sir" a couple of times, but I failed the break the fellow's sweet slumber. Of course, he came into the screening 5-10 minutes late, soon fell asleep, and after at least a half hour of snoring, he promptly left the auditorium as soon as he finally woke up. (And that was just the most egregious example of a pile of small discourtesies at a recent screening of Vanina Vanini...) Also read this ...

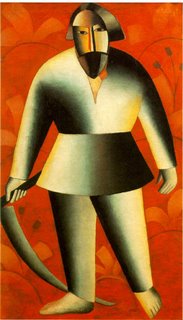

Kasimir Malevich, Reaper on Red Background, 1912-13.

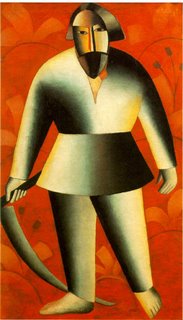

Kasimir Malevich, Reaper on Red Background, 1912-13.

A paradox:"In his last works, Rossellini loses interest in art, which he reproaches for being infantile and sorrowful, for revelling in a loss of world: he wants to replace it with a morality which would restore a belief capable of perpetuating life. Rossellini undoubtedbly still retains the ideal of knowledge, he will never abandon this Socratic ideal, but he does need to establish it in a belief in simple faith in man and the world. What made Joan of Arc at the Stake a misunderstood work? The fact that Joan of Arc needs to be in the sky to bleieve in the tatters of this world. It is from the height of eternity that she can believe in this world. There is a return of Christian belief in Rossellini, which is the highest paradox. Belief, even in the case of holy characters, Mary, Joseph and the Child, is quite prepared to go over to the side of the atheist."

--Deleuze, Cinema 2: The Time-Image (trans. Tomlinson/Galeta, p. 172)I don't know how much I agree with the above passage, in part because I'm never totally sure I understand what Deleuze is talking about, and also (here) because I haven't made up my mind really about "late Rossellini," other than that it's likely one of the peak achievements in cinema. But I wanted to mention it here because I have been thinking about it and want to suggest that Rossellini be discussed in terms of his rhetorical strategies as a filmmaker of which an engagement with realism is one part, rather than being a "realist" who went astray, or who became a "minimalist." Meaning--Rossellini's films are expressions at certain points in his life of a drive to "believe in the world," which could maybe try to build some kind of important direct line between image and referent, but might also be a case of deliberate and remarkable "artifice" (his Joan of Arc film with Bergman), or his late work as an offering of morality--or as I'd put it if asked to do so without thinking for a while about it, an exercise in logos, rationalism, and a very subtle historicism. I'll try to unpack that last part at a later date, see what I really think that proposition means and if I really think it holds water.Perversity:"Let us now imagine a spectator unable to follow a film's story line, someone who could only follow the involuntary forms that have managed to creep into the film, that is, its mistakes. This spectator, a kind of experimental delinquent, follows a film composed of obsessional details. Let me serve as my own example. For years I watched so-called Greco-Latin films (toga flicks, with early Christians devoured by lions, emperors in love, and so on). My only interest in those films was to catchs ight of planes and helicopters in the background, to discover the eternal DC6 crossing the sky during Ben Hur's final race, Cleopatra's naval battle, or the Quo Vadis banquets. That was my particular fetish, my only interest. For me all those films, the innumerable tales of Greco-Latinity, all partook of the single story of a DC6 flying discreetly from one film to the next."--Raul Ruiz, Poetics of Cinema vol. 1 (trans. Holmes, p. 60)Once before I touched upon the idea of generic complexity as a spectrum whereby a certain amount of richness might warrant destructive readings, alterations, and behaviors as in the case of Situationist détournement. I'm not intellectually convinced that this reflex of mine is a good idea, but certainly I'm emotionally attached to it. I don't want my Genuine Genre Art attacked and degraded! But this is precisely because my "taste" or my "knowledge" aren't very good shields against certain abrasive artistic effects--effects which may even have worthy social and political ends, mind you. (Relevant anecdote at the end of this post of Andy Rector's.) What's hard for some of us--it certainly is for me sometimes--is to trust in the durability of art ... as though we're afraid our masterpieces can't stand up to criticism outside the parameters we've learned to hold them to (formalist, dramatic, political). Frame a question a certain way, and I will debate vehemently in favor of art's autonomy and the necessity of its freedom. For instance this was the case with my Sátántangó posts almost a year ago, where I questioned the drive to have everything immediately available as exchangeable commodities: the implicit assumption that widespread DVD availability is an unconditional good thing. My fundamental problem was with the mentality which, to me, celebrated the smooth space of the digital marketplace as a way of masking imbalances, gaps, and inequalities present in the 'pre- or ur-digital' cinema, its own broader (but latent) inavailabilities, and the cultural incomprehension that might accompany this vending machine of film history + cultural capital. But any opinions expressed in this line are, insofar as they make up my personal theory (ahhhh, semipsuedotheory) of art and its relation to the world, exist in dialogue with my impulses which (I hope) empower viewer agency. Perverse readings of films, "anti-viewing," deliberate forays into trivia and marginalia ... these are healthy activities. If (film) intellectuals, in the Gramscian sense, have valuable roles to play in film and media culture today--and who knows, maybe they really don't--it is in pointing people to the ways in which people may better know the differences and uses of viewing/engaging/participating/consuming with or against the grain of a work in question. I feel as though people are culturally encouraged to have opinions about artworks without facets to them--"rate it," 1-to-10, as though your own subjective interaction can be viewed as a monolith, as though one can't filter a work through different grids or dimensions, to understand individual shortcomings or the shortcomings of an originary system, or to recognize real achievements within such limitations--'lines of flight' outward, to suggest it in Deleuzian terms. (I'm not blindly embracing pomo contradiction here--there are despicable films I would not recommend anyone to find a way to defend, and which I would actively campaign against in conversation with people ... for instance, by my judgment, We Were Soldiers, or, less offensively if no less ineptly, the recent King Kong. [The original had a lot of awful baggage too, of course.] But I love Zoolander, e.g., even while I recognize that it's part of a system & industry I oppose and all its parody does nothing to subvert this fact.) In other words, it's not my opinion that really has to prove correct, but rather my knowledge of how my opinions work--on a personal and psychological level, and in a social and material sphere. Hence, reading against the grain in ways that Ruiz suggests, or in completely different ways, is a good strategy, a good set of options (not instructions). It's a whole potential world of operations--perhaps one day we'll be very good at it, audiences can learn to appropriate all manner of things according to their own terms (and, importantly, also be very conscious of the fact that they're doing this). This is one of the reasons why the notion of avant-garde traditions is important to me--for its social functions. (The Surrealists, like the Situationists, were all about new ways to engage with artworks.) I don't believe, like Marcuse, that great art always holds a liberatory potential in it. I think that we can call great art that which is durable to the treatment those human beings who have had cause to encounter it.What I'd like to say is that these two quotes, the Deleuze and the Ruiz, serve to me as good reminders to be willing to believe in a film, any film, without ever feeling obligated to grant it the final word.If/when I teach cinema to students one day, particularly if it's film theory, I would love to bring in one of Deleuze's Cinema books and a volume of Ruiz's Poetics of Cinema to the classroom and try to read and incorporate random readings from both books into each other and the day's topic.It may be early 2007 before I come back with another substantial post (or maybe I can get one more out before then). On the agenda for the near future--I will return to the topic of the Baroque, as well as Modigliani, Soviet art and cinema of the 1920s, hopefully some words on comic books, more on Ruiz and Rossellini (not necessarily together), returning to Godard, deeeep breath, and a few other things.

Here is a film that I suspect is like a bottomless pit in that it operates in a very superficial way as a televisual historical drama, but the more closely one looks at its allusions, its narrative and visual architecture, its powerful articulations of an historical moment, one could find ever-richer material, renewing itself before one's eyes. The masterpiece as the "inexhaustible" text more than the "perfect" one ... more will follow on this film but I cannot predict how soon.

Alex on Kiss Me Deadly, noir, Los Angeles, and the military-industrial complex.Over at Antigram, Tom Cruise, Scientology, and Mission: Impossible III (with spoilers!).

Kevin Le Gendre on Alice Coltrane at Wax Poetics (I just recently purchased my first AC album).Robin Carmody: "The Lost Lineage of Rural Liberalism."Tony Conrad on duration (2004), to expand a bit on my comment on The Flicker in the post below.

(a viewing journal)While almost every other NYC cinephile, and many from elsewhere, was sitting before Out 1 this weekend (was initially shut out because I dared wait until a week beforehand to reserve my ticket; damn!; but fortunately I now have my tickets for the March encore, thank you), I managed to see a few other films over the weekend.Rossellini's Augustine of Hippo (1972)--not to my mind a very major film of RR's, its aesthetic interest (the soundtrack, the zooms, the framing) seemed spread thin and to only cluster into fascinating moments intermittently. The shot where Donatists attack a few of Augustine's underlings (passing out bread to the peasants in the countryside) is an amazing example of zoom & subtle camera movement, for instance.(Before we saw Augustine, some friends and I checked out MoMA's Brice Marden exhibit. Favorite overheard art criticism in recent memory, said in an exasperated, ripped-off tone: "Brice Marden, Brice Marden ... hey, these paintings are all by the same artist!")Robert Breer films; I had seen this program back in January, and it was just as great this time around. Breer himself was in attendance for some reason or other, muttering about how the focus was off. People were clapping a bit between each film and after the third or fourth time Breer announced to his companion, "They wouldn't do that if I wasn't here." The artist's final verdict: Anthology's prints were a bit washed-out, color-wise. While certain films in the program (70; Blazes; Pat's Birthday) have slightly more of an immediate impact for me, again, I think it's Fuji that best summarizes and demonstrates what makes Breer special, and what appears to be the key themes and formal tropes of the preceding two decades. Now if I could just see Breer's late work ...Bruce Conner's A Movie (my third, fourth, or possibly fifth viewing), Conner's Report (first viewing), and the whole reason I went to Anthology that evening, The Flicker by Tony Conrad (relevant to the paper I'm finishing up this week). A Movie is absolutely great, of course, high-energy artisanal melodrama ... in comparison Report extracts the analytical impulse of the earlier film and focuses it more intensely upon its object (media surrounding the JFK assassination), so that the repetition of fetishized a/v footage becomes the material itself, makes it weirder as well as rubbing in its familiarity. The cultural associations one has with a film like this make for a reverberant sort of experience.As for The Flicker, well, as I've mentioned to a few people already, there was one point in the screening where I said to myself, "I honestly don't know if I'm five minutes into the film, or twenty-five." Of the flicker films of the 1960s-70s I've seen, this is the one where individual perception is most forcefully and purely isolated and foregrounded as a component and structuring device of the artwork itself.

"Why make images? Why not be satisfied with embracing reality? Experimental films have often formulated and more often answered this fundamental question in art. Cinema is not necessarily an echo chamber (Jean-Luc Godard's "damsel of recording"). It can be an act; it can become a weapon; it can even get lost in combat. Consider René Vautier's sublime works: designed like missiles to destroy the enemy (capitalist exploitation, to be brief, especially in its colonial forms), they burst into flames, they get blown to bits in mid-air (shots from Vautier's films constantly reappear throughout militant cinema); or else, having accomplished their mission and self-destructed, the work merges into its own concrete historical effects. It would be useful to study the history of forms that brought about militant practices in cinema, whether they came from direct intervention (René Vautier, Chris Marker, the constellation of collectives that blossomed at the end of the '60s, Bruno Muel, Dominique Dubosc...) or from a more classic activity such as pamphlet writing, a struggle against a state of affairs, beliefs or even the image itself (certain cool-headed films superimpose these three targets, including masterpieces by Maurice Lemaître, Marcel Hanoun, the Dziga Vertov group, Djouhra Abouda and Alain Bonnamy, Dominique Avron and Jean-Bernard Brunet). Making images nobody wants to see, offering images for things that don't have any, going even farther than transgression or subversion, experimental cinema confronts the unacceptable, be it political, existential, ideological or sexual. Even these purely nominal distinctions would be obliterated, first by underground cinema, for one (Etienne O'Leary, Jean-Pierre Bouyxou, Philipe Bordier, Pierre Clémenti...), and later by individual personalities like Lionel Soukaz."

-- Nicole Brenez (of course), from the Introduction to Jeune, dure et pure!  Above: Vautier. I really like the idea of one's work living on anonymously by being collaged by others in spirits more or less true to your own.

Above: Vautier. I really like the idea of one's work living on anonymously by being collaged by others in spirits more or less true to your own.

... has to be one of the most exciting film theorists working in American academia. (I say 'exciting' only if you're interested personally or professionally in film theory. His prose is often dense and dry, though never obscurantist: he's always aiming for clarity, he's just often trying to describe very abstract or multidimensional concepts.) Over the last several months I've been picking through any of his articles that I can find, slowly, and as a result I have read the majority of the early published versions of the pieces that constitute his new book, The Cinematic Mode of Production, which I suppose is finally available. I've mentioned Beller here a few times in the past, and have linked to some of his work before."The Spectatorship of the Proletariat," which I have not quite finished yet, is a thick, leisurely paced essay on the creation (and presupposition) of cinematic spectatorship as a form of labor. Let me explain this one roughly, possibly brutally, just to give you a sense. One of the general arguments is that Sergei Eisenstein conceptualized the audience of his films much like machines or animals. Taylor thought of maximizing efficiency of workers in the (macro) factory, and Pavlov thought of understanding machinic impulses in the overriding (micro) mind. (Cinema is the factory or the mind!) In these cases there is a hierarchy constructed by which one class, the filmmaker or scientist, presupposes a certain environment in which they can "manipulate," and perhaps "better," their apparently less well-developed cogs in each system. (I would stress that any initial criticisms of this model should be addressed to my characterization, not Beller's, not until you've read his work.) Beller situates Vertov in opposition to Eisenstein here, a pretty traditional "rivalry" in itself, and I think he's more sympathetic to Vertov because Vertov respects the autonomy of the viewers to use cinema to figure out relations between objects, commodity, labor, value, etc., whereas Eisenstein tries/tried to "play" the audience. But I can't yet be 100% certain that this is accurately Beller's assertion. The piece needs closer analysis than I'm really able to give it at the moment.I hope more will follow here on EL. Some other things he's written:"Cinema, Capital of the Twentieth Century.""Numismatics of the Sensual, Calculus of the Image: The Pyrotechnics of Control."Review of Diverse Practices: A Critical Reader on British Video Art.Review of Fight Club.There are more essays which are not readily available online (or off) outside of a library or education institution with access to certain databases (Project Muse, Ingenta), but a Google search will reveal these and if you can get yourself to a place with a subscription to these services, there will be perhaps 4-5 more articles available.

In this very rare Rossellini film, fortunately presented in the current retrospective, I became more intimately attuned to Rossellini's framing. If you go here you'll see that le Colonel asserts that "the technology allows you to create a very busy, detailed, turbulent mural representing the trenches at the Somme, and it allows you just as easily to introduce a clean blue bunny rabbit or a gnome or a fairy into that hyperrealistic environment, the big, busy, dense, swooping film image with disconcertingly uniform and crisp focus." Everything becomes allegory. With Viva l'Italia, a commemorative film of the 1860 Garibaldi exploits, there are several battle or reconnaissance scenes that take advantage of the mountains of Sicilia or southern Italy, presenting huge vistas where large-scale combat sometimes takes place. These battle scenes are superb, and the reason why is not because they're "exciting" or "psychologically-resonant" (codewords for, this film presents battle as riveting!) but because they foreground the limitations of the frame in the process of presenting their images. The difference between Viva l'Italia and something like The Lord of the Rings is that the CGI battles in those Peter Jackson films suggest clarity and predetermination. You--"we"--know that the camera is going where it has been deemed to go, to capture the appropriate action. It's taking something huge and violent and chaotic, making it clear and readable and even fun. But we never know when or where something--a crowd of soldier's, a main character, a building in the foreground, a lake in the distance--will break Rossellini's shots and basically reconstitute the nature of the entire shot itself, which may have started tight and close but ended long, wide, striated. This is part of his engagement with that amorphous thing, 'realism.' It's not about naive indexicality of the image, it's about the demonstration of material largeness and the inadequacies (as well as attempts) of the camera to capture it all ...

For a few friends...

"Argento's lurid, saturated colours lack nuance and assault the sensorium in their perverse mimicry of the Disney cartoon spectrum. Red predominates in a variety of vibrant shades. It is first glimpsed fleetingly, on an anonymous woman at Frieburg airport where the heroine, American dance student Suzy Bannon, arrives. Suzy next sees red on a terrified student fleeing the dance academy. Red stains the outside of this building, spreading via the wallpaper and drapes as well as wine, blood, fingernails and lips. Violet-blue velvet covers the walls and adds tactile to visual potency. This Technicolor palette drains the strength of the good characters by absorbing their life energy and glowing brighter afterwards. It vibrates in us intensively, oppressing yet arousing us." (p. 142-3)

"Anamalous forms of life invade the dormitories. Their repulsive tactile qualities are emphasised by the sensitive skin exposed to them as the dancers undress. A bat flutters down onto Suzy and clings tight, biting her. Hundreds of maggots appear, wriggling and crawling over the floor,a nd the girls are compelled to tread on them, squashing them either with their shoes or with naked feet. The maggots land in the girls' hair and crawl on their skin as they struggle to brush them off. The use of close-up in this sequence intensifies the viewer's virtual sensation of slime, squirming larvae and viscous texture, particularly repellent on bare flesh." (p. 143)

-- from Anna Powell's Deleuze and Horror Film (Edinburgh UP, 2005)

There are few places on the Net to get as good a giallo education as Killing in Style, it seems to me.

What have I learned from gialli, not that I've actually seen very many? It's good to drink J&B, and it's not a good idea to cross women or animals. (Two stills above from Sergio Martino's Your Vice Is a Locked Room and Only I Have the Key, '73.)

What have I learned from gialli, not that I've actually seen very many? It's good to drink J&B, and it's not a good idea to cross women or animals. (Two stills above from Sergio Martino's Your Vice Is a Locked Room and Only I Have the Key, '73.)

Bill Gunn's Ganja & Hess (1973) is, like Sweet Sweetback's Baadasssss Song, a disjointed and artful example of the serious black genre film of the early 1970s. But whereas Sweetback told a very simple narrative in a very fragmented way, accruing for itself much moment-to-moment richness, Ganja & Hess is allusive, evocative, lyrical, mythic, and complex. One flows with the stream in Sweetback, even when you hit the rapids. Ganja & Hess is like a pond or a swamp or an estuary--a whole complex "ecosystem" is just lurking there under a pokerfaced still surface.

Some aspects of Roberto Rossellini ... triggered by a double bill of Blaise Pascal ('71) and India ('59).Mystic: A deeply spiritual filmmaker; Nicole Brenez described in her original Movie Mutations letter that Stromboli ('50), whose religiosity offended her leftist anti-clericalism, provided a experience to be scaled like a mountain. It took effort for her to let Rossellini "in." Rossellini is not necessarily concerned with miracles as a rule, however: in his work faith is applied to that which perfectly natural and phenomenological, but whose significance comes out, creeps up, overwhelms the characters and the viewers. Socratic: Blaise Pascal really got me thinking about Rossellini as a Socratic filmmaker. To bring up Brenez again, in her piece on Godard in For Ever Godard she mentions how Godard likened Rossellini to Socrates--'a guy who just asked questions.' Throughout his cinema there are defenses of a free spirit, denunciations of any kind of persecution which limits questions. Formalist: amidst ostensibly unfussy, competent frames we will see a camera movement or a composition slowly fall into place which is breathtaking, as time unfolds we may be aware that Rossellini's kino-eye is submerged within the fabric of all his shots. He's not a showy filmmaker, but there are moments where the rigor comes through, because the images' feeling of naturalism periodically dissolves before our eyes.Blaise Pascal is part of the often low-budget early modern costume film stratum that seemed to flourish in the late 1960s and early 1970s. In its pulpish forms (such as Matthew Reeves' Conqueror Worm/Witchfinder General and various other torture movies), this barebones staginess often served to underline sensationalism (a cut to or from a gory image; the presence of a violent or erotic shot). That is, unlike something like Elizabeth (Shekhar Kapur, '97), the images for these kinds of films are often clean, the sets and costumes may be sufficiently ornate but the filmmakers aren't usually going for complicated, deep, sophisticated, lush, porous images, but for flat or simple-perspective ones. Things are spare, and on the soundtrack you can hear footsteps. There are more "artful" early modern costume films of this era, of which Blaise Pascal is an example, who use some of this (possibly budgetary) "plainness" to foreground really ineffable ideas and tones--I'm thinking also of Winstanley ('75), The Immortal Story ('68), A Walk with Love and Death ('69), and the medieval-set films Lancelot du lac ('74) and Blanche ('71). (A counter-example might be Ken Russell's more "baroque" compositions in his amazing film The Devils, or Has' Saragossa Manuscript.)

More coming on Rossellini soon. This is just a still from what is probably the most beautiful shot in India Matri Bhumi ... and one of the most beautiful shots in cinema, possibly.

Stop me if I've posted this one before. Actually, don't. It's worth re-reading!"What, however, can possibly link these two other facts: that on the one hand in the 1960s a handful of middle-class connoisseurs successfully combatted headache and eyestrain to achieve, no doubt, an "expanded vision," an attentiveness to the marginal functionings of their own optic system under stimulation and that, on the other, the large plebeian audience of the first ten years of motion pictures put up with a flicker that their social "betters" regarded as such intolerable discomfort that it contributed to their staying away in droves from the places where films were shown ... those smoke-filled, rowdy places frequented exclusively in those days by a class of people for whom motion pictures were cheaper than an evening at the gin mill and no doubt somewhat less uncomfortable than a day spent in the racket and stench of the factory of sweatshop?"In any but a purely contingent sense, there would seem to be no link at all here, and in fact any attempt to establish one might seem at best ahistoric, at worst grotesque. Yet I have come to regard this encounter as emblem of the contradictory relationships between the cinema of the Primitive Era and the avant-gardes of later periods. For the elimination of flicker and the trembling image, fairly complete after 1909 it seems, was a crucial moment in the realization of the conditions for the emergence of a system of representation complying with the norms of an audience which would include various strata of the bourgeoisie. When the successive modernist movements set about extending, pragmatically or systematically, their "deconstructive" critiques of those representational norms to the realm of film, it was inevitable that sooner or later the flicker should reappear, valued now for both its synthetic and its "self-reflexive" potentials."--Noel Burch, "Primitivism and the Avant-Gardes: A Dialectical Approach"

Diego Velázquez, La Venus del Espejo (1648-51)

"This nakedness is not, however, an expression of her own feelings; it is a sign of her submission to the owner's feelings or demands. (The owner of both woman and painting.) The painting ... demonstrates this submission ..."

-- John Berger, Ways of Seeing, p.53 (referring to a different painting)

The above image is the figure of a woman who exists for no more reason than the leisurely contemplation and enjoyment of her own beauty, i.e., the satisfaction of herself not as self but as an object of sight. I haven't done enough research to make an educated guess on Velázquez's motives, but regardless of them, I can suggest that the image offers a way out of the unsavory tradition of the Western nude: that by presenting the woman's back to the spectator, and the face as a blurry reflection (also optically impossible), this Venus is presented as obviously an object, immediately and apparently an image for our pleasure and consumption. An iconographic explication of the presence of the mirror might indicate the theme of vanity ... but we can't intuit any emotion or thought to this Venus. She's gazing into a mirror, taking in her own beauty and objecthood, but we are not presented with psychological evidence of her (moral failing of) vanity. She is Image: her Imageness is manifest.Idle speculation: I have not yet read Deleuze on the Baroque: but if the Baroque is marked by some kind of figure of "the fold," is the productivity of our latter-day engagement with the Baroque marked by our willingness to 'unfold' what was hidden in the folds? That is to say, in the complexity of (say) an image, an oil painting, in the later 17th century, might the interest to us, post-contemporaries, be in the accordion-like flexibility that this furled-up information pack (or stream) provides us? It's what I'll be thinking about in the future. Maybe I'm completely wrong.

Above is an image of Mary "Slasher" Richardson, who attacked the Velázquez with a meat cleaver in 1914. She was a militant suffragette; according to this white nationalist forum page she was also a supporter of the British Union of Fascists and National Socialists.

An excerpt from Paul Sharits' N:O:T:H:I:N:G on YouTube, from a user named 'Afracious.' It seems to take a little while to load, so please be patient!

You can find a lot of his (earlier) stuff on YT, in full or in excerpts, including T,O,U,C,H,I,N,G (the one with the scissors-to-the-tongue). I haven't really watched much of it because of these blurry, artifact-laden transfers on a computer screen simply can't approximate the sheer enveloping force of the flickers projected in a theater. But, as I've mentioned his work periodically in the last few weeks or months, I figured I'd point this out to anyone who may not know anything about Sharits but would be interested in sampling the films (if in a compromised form).

In Desire (which Rossellini began filming in 1943 but which was finished by Marcello Pagliero in 1946). I don't know how much of Rossellini's work actually survives in the cut shown at MoMA, but it certainly feels like a Rossellini film to me, and a masterpiece, at that. Regardless of who helmed the scene, there's a quick moment where the protagonist Paola (Elli Parvo) is walked home by her gentle Roman beau Giovanni (Carlo Ninchi); she has told him earlier that she has to leave Rome to return to her family's place in the countryside. There's a medium shot of them walking side by side. Cut; they're at the door; Paola's back to us. She turns around and she has tears in her eyes. Absolutely nothing about the composition of the shot or the tonal thrust of the moment centers the tears. If you walked into the theater late and saw this scene immediately you would not even expect tears. But the sudden bursting-forth of this undercurrent, the presentation of a truth beyond appearance, is precisely what Rossellini could get at with incomparable skill.There are a few shots that look as though they're in slight slow motion; they're incredible.There is a constant presence of wind and breeze in the outdoor shots.This film is too beautiful, its beauty is too powerful.

Re: the image above, you know why.

This has got to be the most I've ever posted in a single day.

Let's assume that someone is looking up Schrader's canon online in order to have a nice checklist for the cinema. Perhaps Google or somebody else's website will direct them, in their search, to my blog? My criticism of Schrader's rhetoric and his choices is already up & available, so now what I want to do is propose a counter-canon. Perhaps someone--a budding cinephile, an older person who is just deciding to watch film seriously, an enthusiast of a certain era or genre who wants to branch out more generally--will see Schrader's canon. And there are some great films to see there! But for the purpose of education, encouraging people to see a variety is at least as important as getting them to see The Greats. So that's the first purpose of this list: not to winnow away toward's film art's great core (which I am unconvinced even exists), but to sketch an idea of this medium's powers & parameters. Secondly I want to tweak Schrader's own conception of a rigorous canon. His isn't highbrow by a long shot! There's nothing inherently wrong with middlebrow tastes--unless the person proudly displaying such insists to you that he's got rigorous high standards and a devilishly high brow (as Schrader happens to insist). These are companions to Schrader's sixty canonical films. Complements; supplements. These don't operate as a canon; they are a counter-canon; they are intended to be watchtowers pointing out towards the parameters. They aren't actually the parameters of cinema's power, though. Except possibly a few of them. I'm only suggesting some new paths to travel, heavily skewed by my tastes. (Even then, frankly, a few films here--the Browning, the Tati, the Eisenstein--do get mentioned in canons sometimes.) When I was whittling down I ended up being least merciful to to Hollywood and French films--which make up the base of my younger cinephilia--because that's what gets the most attention anyway, so there are major films by Sirk, Ray, Walsh, Guitry, even Vigo, etc. "on the cutting room floor." Sixty films in alphabetical order:

3/60 Bäume Im Herbst (Kurt Kren, 1960)Almost a Man (Vittorio De Seta, 1966)Les Amours de la pieuvre (Jean Painlevé and Geneviève Hamon, 1965)

L'Ange (Patrick Bokanowski, 1982)

Arigato-san (Hiroshi Shimizu, 1936)Arsenal (Aleksandr Dovzhenko, 1928)Barsaat (Raj Kapoor, 1949)

The Bloody Exorcism of Coffin Joe (José Mojica Marins, 1974)

Calabacitas tiernas (Gilberto Martínez Solares, 1949)Casual Relations (Mark Rappaport, 1973)

Child of the Big City (Yevgeny Bauer, 1915)The Cloud-Capped Star (Ritwik Ghatak, 1960)Cockfighter (Monte Hellman, 1974)Daisies (Vera Chytilova, 1966)Dark at Noon (Raúl Ruiz, 1993)Day of the Outlaw (Andre De Toth, 1959)

De cierta manera (Sara Gomez Yera, et al., 1978)Docteur Chance (F.J. Ossang, 1997)

Edward II (Derek Jarman, 1992)The End (Christopher Maclaine, 1953)

Forest of Bliss (Robert Gardner and Akos Ostor, 1986)

Freaks (Tod Browning, 1932)

Fuji (Robert Breer, 1974)Hard Labour on the River Duoro (Manoel de Oliveira, 1931)A House Divided (Alice Guy-Blaché, 1913)

Las Hurdes (Luis Buñuel, 1932)

Ice (Robert Kramer, 1969)

Images of the World and the Inscription of War (Harun Farocki, 1988)La Jetée (Chris Marker, 1962)

The Lead Shoes (Sidney Peterson, 1949)

Lettre à Freddy Buache (Jean-Luc Godard, 1981)Love Streams (John Cassavetes, 1984)Les Maîtres fous (Jean Rouch, 1955)

Make Way for Tomorrow (Leo McCarey, 1937)Mandabi (Ousmane Sembene, 1968)Man with a Movie Camera (Dziga Vertov, 1929)

La Marge (Walerian Borowczyk, 1975)

N:O:T:H:I:N:G (Paul Sharits, 1968)

Paul Tomkowicz--Street-railway Switchman (Roman Kroitor, 1954)Playtime (Jacques Tati, 1967)

Le Retour à la raison (Man Ray, 1923)Rose Hobart (Joseph Cornell, 1936)The Saragossa Manuscript (Wojciech Has, 1965)

Score (Radley Metzger, 1973)

Los siete locos (Leopoldo Torre Nilsson, 1973)

The Store (Frederick Wiseman, 1983)

Strike! (Sergei Eisenstein, 1924)Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One (William Greaves, 1968)

Take the 5:10 to Dreamland (Bruce Conner, 1976)

The Terrorizer (Edward Yang, 1986)

This Land Is Mine (Jean Renoir, 1943)Times Square (Allan Moyle, 1981)

A Touch of Zen (King Hu, 1969)Touki-bouki (Djibril Diop Mambety, 1973)

Tropical Malady (Apichatpong Weerasethakul, 2004)

Videodrome (David Cronenberg, 1983)

Le Voyage à travers l’impossible (Georges Méliès, 1904)A Walk with Love and Death (John Huston, 1969)We Won't Grow Old Together (Maurice Pialat, 1972)Winstanley (Kevin Brownlow and Andrew Mollo, 1975)... again, this is not a canon. It's not definited by being the "best" (though I did somewhat de facto limit this to films I felt were genuinely great, excellent, or in some cases just very interesting). This list is meant to work in the spirit of enriching canonical lists. This list of worthy films is meant to point out in many different directions: unlike a canon, which gives people a finite list which they can check off one title at a time, this is meant only to suggest to people a great deal more viewing to do, if they so wish. And it is not my purpose to claim that this list is "better" than Schrader's canon, that the films are better, only that it offers a better picture of cinema's possibilities ...

I wasn't incredibly impressed with Paul Schrader's article on the cinema canon (thoughts here). He has responded to his critics here. (Also, someone signing as 'schrader' did post a comment in reply to my original criticisms, but the person--he, if it was indeed Paul Schrader himself--declined to address my thoughts, answering the great Jen MacMillan only, perhaps because he's decided I'm not worth addressing. Fair enough.) In Film Comment now, the man writes:

"I wrote the article in reaction to this, attempting to look back at the Century of Cinema with a cold eye and a very high brow."

Schrader's canon is the definition of middlebrow, not highbrow. This is basically an inarguable fact about his choices as far as I see it. His canon offers us nothing new: he's reiterating a standard greatest hits list of a decently educated middlebrow film buff contingent, as any Film Comment reader has doubtless already seen countless times in places like Sight & Sound. He adds a slight personal twist by including films like The Big Lebowski or Talk to Her instead of absolutely anything that is short, nonfiction, or avant-garde. Apparently Schrader would have us believe that highbrows hew to the mainstream feature fiction film and nothing else. Ha! (And he happily owns up to the charge of Eurocentrism in the process, weirdly enough.) I wrote a huge draft in response to Schrader's own response to his critics, but I've basically deleted it. I made a lot of my major points already and I don't want to keep harping on them. Instead I want to offer something positive instead of further rants. For anyone young or new to cinema who might google 'Schrader's canon' in order to look up films, and who might come across this page, I'm going to offer a counter-canon. To me, adherence to a canon is less important than instilling/encouraging comprehension, critical thinking, curiosity (three c-phrases I prefer to "canon," now that I think of it) as far as pedagogy and film culture are concerned. Instead of the films Schrader's chosen, I'm choosing deliberately less well-known, offbeat, perverse, even strenuously imperfect "b-sides." Some of them are greater, perhaps much greater, than their counterparts though. But as I've said, I do love some of his choices, so other b-side choices are not meant as replacements but rather as supplements or complements. I'll see if I can get a counter-gold section up tonight.

Exhibit A:

Exhibit B:

Exhibit C:

I'm not trying to bear pretensions toward knowing anything out of the ordinary about race and racism--because I surely don't--but this Michael Richards incident has come out at just the time that I've been reading and thinking a lot about images and conceptions of blackness in my country's cinema and popular culture--obviously. So. The problem I have here is the widespread cultural assumption--basically held by white people--that being a racist is almost an "occupation," that Michael Richards can claim with a straight face that he's "not a racist," yet that that these words just "bubbled up." (Perhaps had he dropped the N-bomb alone one could chalk it up to a racist action merely fueled by a misguided attempt to "shock," as though he were just following in the fearless footsteps of Lenny Bruce or Richard Pryor. But the furious, and initial invocation of a lynching murder--a fork up your ass!?--just confirms something deeper.) This is the sort of irrational mentality that justifies statements like, "I'm not racist, but..." But what? As though pre-emptively asserting that you're not a racist nullifies the vicious idiocy of the racist statement you're about to make?

One of those trashy reality TV shows--was it an episode of America's Next Top Model?--had one white "contestant" (or should we 'fess up and just call them characters?) spewing racist cant: no dreaded "n-words" if I recall, but a lot of stupidity about (y'know) those types of people--welfare mothers, FUBU clothing, all the regular caricatures promoted by Limbaugh-types. When some of the other contestants called her on this, including, particularly, a black woman, this racist insisted to the other contestants that they couldn't accuse her of racism because she knew in her heart that she wasn't racist, you see, and since they couldn't know the state of her soul as well as she did, they couldn't be sure that she was a racist. This is the belief: that being a racist can only, strictly mean one who actively lynches blacks people, uses racial slurs openly, and willfully admits that he or she thinks whites are superior to all others. Nobody else is racist by this illogic: actually racist behavior, for instance, is by the same token dismissed as 'mistakes,' 'accidents,' 'misunderstood actions.' Never for what it is. (I believe the unsavory aspirant was eliminated early from the model comptetition, by the way.) In an interview Stephen Colbert said to Tim Robbins recently, "You're white, right, 'cause I can't tell, you know. Race doesn't matter to me, I can't even see a person's color." A typical rallying cry for my fellow whites well-caricatured by Colbert there.

So look at the spectacle we have before us recently with regards to Michael Richards' outburst. I'll handsomely wager he doesn't have a KKK hood in his closet. He's not some vigorous, full-time, Aryan Nation-style racist. But his behavior is simply an outcropping of deep-seated racism embedded in the power structure of this society (which his "apology" very vaguely acknowledged, albeit as a way of rationalizing his actions). What interests me also is that Jerry Seinfeld was so shocked and saddened by this outburst (and the forthright, unignorable racism of a certain word), but as the Danny Hoch video above demonstrates, he is no angel either as far as the propogation of racism in art and media. It's not enough to allude, as Richards does, to some kind of wounded Zeigeist which we need to heal--that's true enough, in its cloudy ethereal way--but to also identify those instances, material and recognizable instances or practices, when this racism against all people of color comes through in ways less immediate and blatant (to nonwhites) than a single word, like "nigger." Racism also means something like "Ramon." Nonwhite individuals & communities of course are sensitive to these instances, already, and have long been. How can they help get the rest of us to pay attention?

I "discovered" Willem Drost in a course on Dutch & Flemish painting I took in college. I prefer his version of Bathsheba (1654) to his master's (although I have never been to the Louvre and have never seen either in the paint). The roundness of the forms of this solitary woman, placed within an asymmetrical composition, makes for a very subtly unsettling image--as though balance has just been lost.

So Tuwa saw Sweet Sweetback's Baadasssss Song the other day, and following his lead, so did I (this was my second viewing). Why the crazy film grammar? I haven't done the research that might give us a really satisfactory answer, but let me speculate a little first, then I'll post a few facts about the film's production. Maybe a little later down the line I'll post more with some reading under my belt.It's interesting that this film has come up on EL just at the same time I've posted the Sharits image (and, uh, "dialogue excerpt") from T,O,U,C,H,I,N,G. We know, and can trace, the loose netting of connections between the low culture 'generic' or 'exploitation' film by the very late 1950s or early 1960s into the 1970s and those of the high culture 'modernist' (including, even, 'structuralist' or 'materialist') cinema of the same time. The experimental elements of classy Metzger (a swingin' and cocktail-slingin' Resnais) or trashy Meyer (a Mojave desert trucker-Eisenstein), for instance. A fellow cinephile on the Net, many months ago, suggested I check out Vernon Zimmerman and Andrew Meyer, who both began in the a-g but moved into exploitation. Andy Milligan? Jack Smith? So many possibilities, and I'm only mentioning (mainly) American work thus far. Sweet Sweetback boasts a straightforward narrative through-line: Sweetback, who has had a tough live but possesses great sexual prowess, is sold out in a to-be-minor way by his (black) employer, only to "break," and find himself on the run from the police. Moment to moment, though, the film is disjointed, repetitive, "crunchy" rather than smooth. At one point in the film a woman complains about how, when her children get old and bad, the government takes them away from her--she might have had one named Leroy, but she can't rightly recall. On the soundtrack her couple of lines are replayed, with slight variation as to where they might stop or begin, at least a half a dozen times. What's the reason for something like this? What's the rationale behind stray cuts and nonlinear throwaway footage in Melvin Van Peebles' film? I would suggest that it's got something to do with whatever also inspired the likes of Snow. For this question I'm moved to suggest that the issue at hand isn't one of Everest-like aesthetic experimentation "trickling down" from the contemporaneous high-cinematic heroes of Manny Farber and Peter Wollen circa 1971 to the supposedly lower forms of Russ Meyer's bosomania and MVP's struggles against The Man. Rather it's a multi-front assault, where fringes of popular cinema--the trashy, the generic, the rebellious--working on, in their own way, the sorts of problems that artists like Sharits, Snow, et al. are expressing at the same time. (Again, let me emphasize I'm dealing mostly with an "American" scene--North American, if you will--for convenience's sake more than anything else.) Sweet Sweetback is dangerous in part because it doesn't connect its critique of racism to a nice narrative that we can enjoy thoughtlessly ("we" here meaning white viewers, at least; I can only idly imagine how various non-white audiences saw and see the film). It's a brutal narrative, a story about ruthless domination, relentless pursuit, and unsolicited survivalism. The story almost has to be fractured on an experiential level (and simplified on a conceptual one) in order to deliver the real ... I hesitate, but: meaning ... of the film. That is to say, the tool of the three- or five-act narrative, with three-dimensional characterization, seamless pacing and continuity editing, which historically suits the fiction feature film so well, is usefully fractured in this particular fiction feature film because it renders more palpable the offenses dealt to its characters (and by association "The Black Community," credited as stars in the film, of course); it depicts more nakedly the structures and enactment of racial aggression and domination that whites, particularly powerful whites and their servant classes whether brain or brawn (not all white characters in the film are "enemies" though), carry out. The narrative doesn't carry us, we have to sit and watch each abuse, hear each sad or angry line, for what they are--and as pulled stitches out of what we may prefer to be a seamless narrative.In short, my preliminary guess as to why Melvin Van Peebles made this film the way he did is that the techniques offered a utilitarian solution to his expression of flight, struggle, and solidarity in the face of the American racial/social structure. This is not to say that I think MVP didn't also have strong aesthetic interests in such techniques, too: he might have, much like someone like Sharits. But the pragmatic usefulness of these techniques seems to me to be a pretty unavoidable justification. (I haven't seen Story of a Three Day Pass yet, but the more traditional film Watermelon Man seemed pretty unsuccessful to me. It's worth seeing if it falls within one's personal or scholarly interests, of course, but I can't say it's quite as damning and--this is important--motivating an indictment of American race relations as Sweetback is.)* * *"Stating that what major studies like Columbia Pictures, which had offered him a three-picture contract, called a little control he called extreme control, Van Peebles dropped the contract to make a "revolutionary" and independent film. Produced for $50,000--the money he had earned as director of Columbia's Watermelon Man, a loan of $50,000 from Bill Cosby, and funds from nonindustry sources--Van Peebles's $500,000 production, Sweet Sweetback's Baadasssss Song (1970) changed the course of African American film production and the depiction of African Americans on screen. ... Unlike the experience of Gordon Parks with Warner Bros., Van Peebles avoided paying film industry craft union wages by claiming to be producing a porno picture. He also wrote and directed the film and composed the music, in addition to playing the leading man. Released through Cinemation, initially in only two theaters, one in Detroit and one in Atlanta, Sweetback grossed over $10 million in its first run."-- Jesse Algernon Rhines, Black Film/White Money. Rutgers UP, 1996. p. 43-44. [Sic on the figures mentioned, by the way. I think that the first $50K might be a typo, that is, $500K?]

"Destroy. Destroy. Destroy. Destroy. Destroy. Destroy. Destroy. Destroy..." (And check out this.)

Eventually I hope to turn this train of thought into something. Anyway, a clumsy start:

(The Scar of Shame, 1927, directed by Frank Peregini. I understand Micheaux's predominant theme was 'passing'--I've only seen one for myself; this similarly seminal film of the silent black American cinema, on the other hand, is foremost about class and color tone divisions among black people exclusively, if I recall.)

Fred Hampton after he was murdered by the police.

Superfly.

"Don't fuck with Pam Grier," we are told forcefully enough by images like these.

What I'd like to suggest, one topic or tangent I want to introduce, is the question of black Americans' "space of their own" in cinema--that means literally on-screen but also in terms of exhibition or consumption. There was the cinema of Micheaux and up through Spencer Williams, Jr.--respectable cinema, or so I suppose its reputation holds, for and usually by black people. The 1960s (David Ehrenstein relates here that Billy Wilder's The Apartment was a watershed moment for the hiring of black extras in H'wood, by the way) had what I figure to be an entrenchment of two dominant cinematic/media image-sets of blackness in America. There is blackness as a well-behaved victim (child or chaste adult), Mockingbird blackness, Poitier blackness: truly dignified at best, horribly condescending and racist at worst. Perhaps both at the same time, quite often. Then there is blackness as a threat, very strong and masculine and separatist: the Black Panthers, for instance. I could be wrong about this: I'm still a fumbling student of the issue: but it's my impression at the moment.

The black exploitation film as a tool in the process of social control?--better for a dominant white class to peddle fantasies of black power to black audiences after so many of its political leaders had been assassinated, than to have said leaders making real strides. What became "blaxploitation" started off as a tool, an expression, of black individuals and communities. Melvin Van Peebles made Sweet Sweetback's Baadasssss Song ('71) on his own. And it was attuned to something deep, powerful. But around the same time, Hollywood was allowing black people to finally make their own films--under the aegis of Hollywood and its money, presumably for black audiences, but not independent for themselves. Gordon Parks made the first such film in The Learning Tree ('69, a good film though I saw it years ago, don't recall it too well). Blaxploitation soon became a moneymaking tool for your standard, white-owned, white-run companies. Black actors starred in movies (at least nominally?) targeted to black viewers, but by and large I don't believe these films produced for the black community/ies of America.

What I want to critique--assuming there are not parts of the equation which I have yet to discover which would negate the basic criticism--is the exploitation of distinctly black film workers and audiences for distinctly white profit. But. I don't want to dismiss this genre altogether for the circumstances of its production. I want to look into it, see more than the handful of films I have already seen, figure out what it says and what it might say. I would like to learn to what extent, and in what nature, the genre might have been a genuine "space" of black Americans' own. I have a decent initial grasp of the available bibliography, but if there are hidden gems to be read (or seen), please let me know. I also did not see Mario Van Peebles' recent documentary, though I will. This is the foundation: what I want to go into is analysis (or even "poetics"--a non-Bordwellian sort of film poetics?) ...* * *... and ... on the nature of Elusive Lucidity these days, I have to admit that I am apprehensive of alienating the small group of people who read this blog. I am grateful for any and all readers I have (though at the same time I basically dislike bringing up my work to people who don't know about it: I feel the only readers I earn are those who find me and decide the writing is worth a return peek). I know that this is essentially a cinema blog. And I want to keep this a cinema blog, because if I am good at keeping a blog about anything, it must be that. But for months now (actually, really, maybe it's a process of years) I have felt a mounting personal pressure about politics, and greater and greater self-resentment for not doing anything about it. I feel a paralysis because of this--a paralysis of my creative and analytical faculties both. When I read sites like Venezuelanalysis, Brownfemipower, Corpwatch, or countless others, I am overcome with the urge to have my own meager screen musings online reflect the passion & hopefully commitment that these sites--these people--inspire in me. (As to how well I translate that into real life, too, well, that's another part of the challenge.) I make zero apologies for my politics; at the same time I make zero demands of my readers, politically. I understand that there are a few conservatives and libertarians, and probably a majority of liberals/Democrats, among my readership, and I consider myself none of these. So in discussing moving images I hope that my hospitality and my convictions work together organically, and I hope that I can essentially, eventually do more than preach to a choir either politically- or cinephilically-speaking. There--that's off my chest with #201.